The aim of territorial cohesion does not call for a new policy that would be added to the European social and economic cohesion policy which is traditionally characterized by its growth and employment objectives. Economic, social and territorial cohesion can be understood as the objective that must be pursued by growth and employment policies as well as, more generally, all policies that compete in the development of the regions and the territories or which have an impact on the territory by seeking to reduce economic, social and territorial disparities within the European Union and promote greater accessibility for all to common goods and public services. For this reason, cohesion policy does not function like other policies as a supplementary constraint on Member States. It pursues a shared objective that only Member State practice allows one to validate.

Concretely, what is this objective? It involves establishing coherence between sector-based policies of generally acknowledged territorial impact and national policies with community objectives. This is the reason why it depends on states that oversee development policy on their own territory and cooperation between these latter and the EU. This shows how necessary it is to indicate where and how these sector-based policies impact the territories and why governance is at the heart of the matter.

In sum, to consider the future of cohesion policy, one must again consider the objective targeted by the various territorial policies, the quality of available instruments and the issue of governance.

It is thus clearly a matter of an objective shared between the Union and the Member States which has increasingly come to be considered a priority objective.

Within the network, we have chosen to treat “cohesion and territories in Europe”. This will lead us to consider, on the one hand, the relationship that exists (or should exist) between sector-based policies, cohesion policy and territorial development and, on the other hand, the contribution that adding the term “territorial” should make to economic and social cohesion in the Lisbon Treaty.

1. Dynamics to Be Taken into Consideration

The Need to Specify Objectives and Content

Preoccupation with the territories in the European Union has been growing since the adoption of the ESDP in 1999. In particular, cohesion policy – which is above all regional development policy – came to take on an increasingly significant territorial dimension over the course of program planning. In Leipzig in 2007, the Member States adopted the Territorial Agenda, an inter-governmental reference document. These movements have contributed to incorporating territorial cohesion into the primary law of the Union (first in 1997 in the article of the Amsterdam Treaty devoted to General Economic Interest Services and then in the Lisbon Treaty). An initial discussion of this subject took place on the occasion of the Commission’s publication of a Green Book on territorial cohesion in October 2008. Today, the Commission is elaborating its proposal for the 2014-2020 cohesion policy, which must take the objective of territorial cohesion into account.

A good number of questions nevertheless remain open, particularly in regards to the definition of the content of territorial cohesion, the common strategy that will allow the economic growth, social cohesion and balanced development of the territory to be harmoniously combined. That constitutes the first dynamic. We need to formulate these dynamics and reconsider sector-based, national and community policies and cohesion policy in order to begin to develop answers. For us, it is a matter of acquiring a common vocabulary that will allow us to reexamine the action of sector-based and cohesion policies in this area.

Territorial Diversity: How Should Instruments and Policies Be Coordinated?

The second dynamic is a matter of territorial diversity. The extent of European variety calls, not only for policy harmonization, but also for deeper cooperation between Member States. Indeed, there are ruptures in the European space that do not depend on geography but rather on the variety of institutional constructions, public policies (fiscal, in particular), frameworks/organizations and administrative rules which crisscross the territory of Europe. Moreover, these constructions may be the product of a voluntaristic policy that seeks to take spatial disparities into account (France’s ZRR and ZFU, for example). Furthermore, the great variety of the territories sheds light on profound disequilibria at the level of the European space. There are very few large cities – those exceeding 5 million inhabitants are home to 7% of the population as opposed to 25% in the USA – even though they contain a heavy concentration of economic activities. This leads to significant negative externalities in terms of urban congestion.

Significant territorial disequilibria result from this: polarization of the territories between urban centers and peripheral zones, urban spread leading to increased overlap between urban and rural areas and the spatial concentration of social problems. What’s more, this variety is based on a large number of geographical particularities, some of which may be seen as a handicap, even if they are advantages from the point of view of tourism. Such is the case of low population territories (counting 2.6 million or fewer individuals), mountain zones (with their 50 million European inhabitants) and islands (representing 3% of the European population). In addition to constituting sites of territorial discontinuity, border regions can sometimes accrue some of the traits underscored above. Taken together, such regions contain more than 30% of the EU’s population.

In order to respond to this territorial diversity, the question arises, not so much of creating new support instruments, but rather of coordinating existing policies and instruments. But how is greater flexibility to be introduced into the existing tools? How is more consensus to be created around them, greater synergy? How are finance tools to be simplified? In the end how are cohesion policy tools to be made more functional? How are we to acquire better calibrated instruments for gathering statistical data? The answers to these questions should also allow us to reaffirm several of the conclusions of the Barca report. We retain from this latter the need, first, to examine the conjoined issue of effectiveness and fairness in the case of all territories (and not just the poorest ones) and, second, to target social inclusion via an updated, territorialized social agenda.

Finally, the question of the relevance of using identical instruments and applying similar programs to broadly different realities arises in connection with the issue of territorial variety. For territories that have never been in a situation of development, what is the value of efforts to combine policies that simultaneously target effectiveness and fairness? What does the promotion of “hidden resources” mean for mono-industrial territories affected by profound economic crises?

In these conditions, what does the objective of developing human capital and lifelong learning mean? Why create transport links in the most remote zones if no spirit of enterprise is in evidence? How are synergies to be created between actors whose resources are far too asymmetric?

2. Programmatic and Practical Responses in Action

One can try to refer to the comparative advantages of various types of responses:

-

In quantitative terms.

-

In spatial terms.

Indeed, models exist concerning these two aspects and must be discussed – for example, forecasting of the effects produced on territorial development by variation in the “intensity of aid” and possible scenarios concerning the spatial forms taken by cohesion policy.

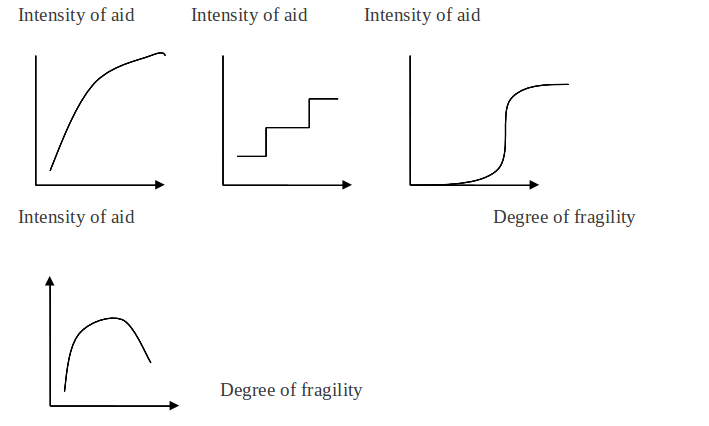

In response to these latter questions, cohesion policy implements responses that depend on the fragility of the territories. It encourages the development of energy and transportation infrastructures, environmental infrastructures in the most disadvantaged regions (cohesion funds), the reinforcement of the environmental implications of agricultural activity and, more generally, support for the ecological initiatives of the various economic activities, that of cutting edge research and the strengthening of transnational research projects. Cohesion is not a matter of simple proportionality. Thresholds may exist, shifts in the nature of interventions. In the same way, there may be asymmetries of treatment (figure 1).

Figure 1: The intensity of intervention can increase according to the fragility of the territory but may also take other configurations (figues 1 to 3). The effect of zoning is to create stages (figue 2). Moreover, one may sometimes decide to favor safeguarding intermediary spaces as poles of development without irrigating all peripheral spaces to the same degree (figure 4).

If one wants to describe and analyze territorial cohesion policies in their geographical dimension, two questions must be addressed: the question of scale and the question of the spatial features of territorial action.

Concerning the first, one observes that new geographical scales of intervention are emerging and constitute potential zones of integration in which a better coordination of public, national and community policy can take place and in which part of the future of cohesion policy is to be forged. These are macro-regions. The landmark example is that of the Baltic Sea, which joins 8 Union Member States and their neighbors around common issues (like the environment, transportation, economic activities, urban networks). This leads one to contemplate the magnetic force of other macro-regions, like the Danube basin, the Alpine space, the Mediterranean space, the Atlantic arc. These are all regions (peripheral or not) in which territorial cooperation is taking place.

As territorial configurations, three forms of organizing territorial action coexist. First, there is “paving”. This refers to a form of action that privileges the regularity of intervention across a more or less homogenous framework (and is intended to cover the entire territory). Paving has its origins in an “egalitarian geography”. Next is the “pole” configuration. This consists in supporting particular points of the territory, whether as a way of remedying serious deficits, in response to an experimental desire to innovate or, finally, to lend a hand at a given place in the belief that the resulting effect will be passed on to neighboring territories by a process of diffusion. The “pole” has its origins in a “priority geography”. Finally, there is the “network”. This consists of supporting families of territories (or groups of actors in the territories) to help them organize among themselves and communicate with one another regarding common or innovative operations. This support can in certain cases take place through a structure representing the network (“the head of the network”) and agreements can be reached with it. The “network” thus has its origins in a “voluntary geography”.