Renewable Energy Sources

4 October 2022

Energy Efficiency

13 October 2022By Cindy VUAILLAT, Isaure VORSTMAN, Théo SEYGNEROLE

The European Green Deal places high importance on offshore wind, and is prepared to make major investments in its expansion in the next few years. Why is the EU so enthusiastic about offshore wind? Is this enthusiasm realistic? We’re not here to convince you, but merely to give you the facts, and let you decide for yourself!

How it works

A variable renewable energy source

Offshore wind is a renewable energy source (RES). Wind, a natural phenomenon, exists independently from human intervention, and is an unlimited resource: we cannot “drain” the wind blowing off the sea coasts. The strength of the wind varies from time to time. This makes offshore wind a variable renewable energy source (VRE).

A straightforward technology

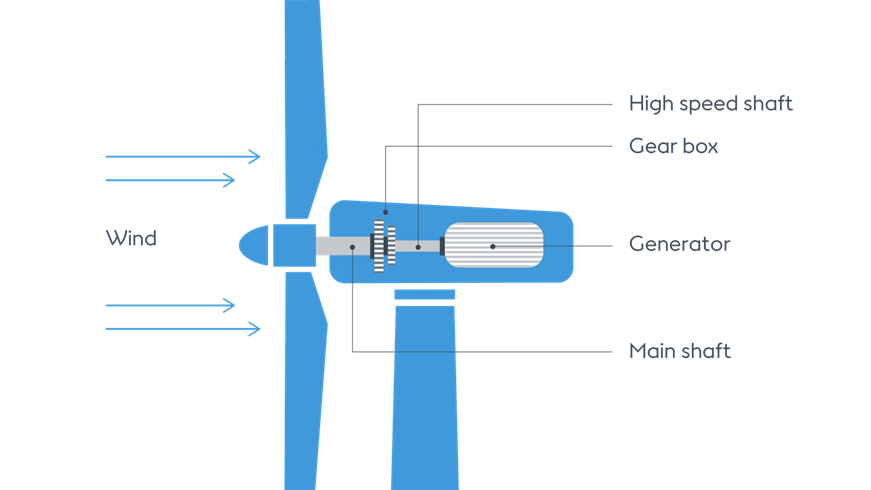

Wind power makes the blades of the turbine spin. Within the turbine, the gearbox increases the speed over 100 times, and the high-speed shaft transfers this kinetic energy to a generator, turning it into electricity.

Fig. 1: How a wind turbine captures energy. Source: Ørsted

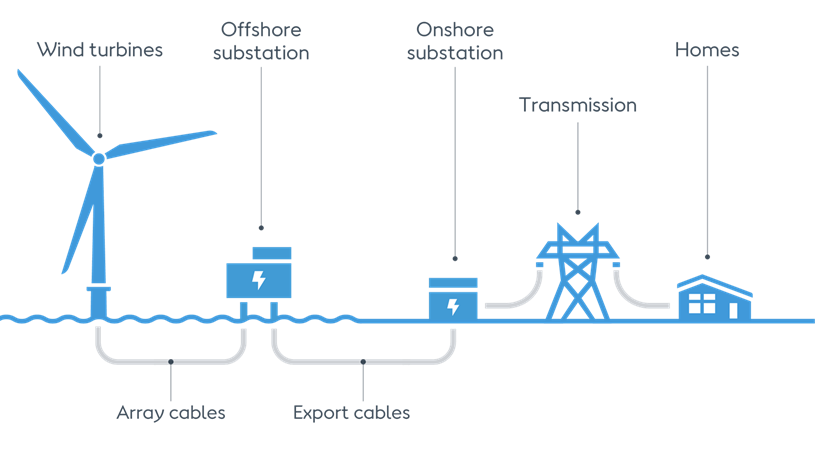

The electricity is then converted, transformed and transmitted via underwater cables from the offshore to the onshore substation, where the energy is converted into a high-voltage current. Through distribution networks, the electricity is transmitted to households.

Fig 2.: How electricity is transported to households. Source: Ørsted

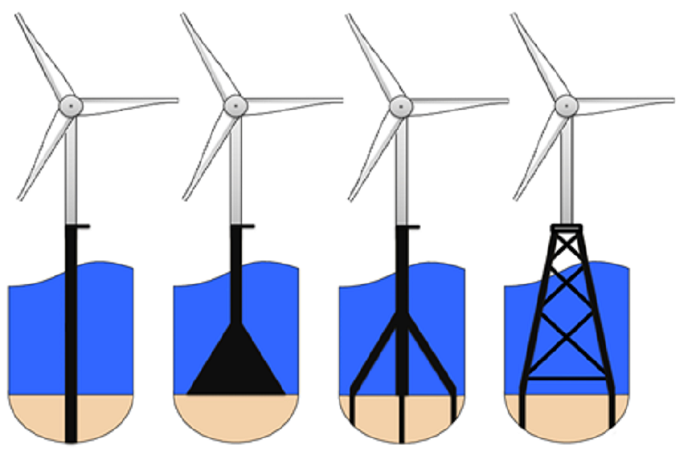

Most offshore wind turbines have “bottom-fixed” foundations, meaning they are fixed into the sea floor. To build such a turbine, it needs to be shipped in parts, and assembled on the location where it is then directly installed.

Figure 3: Bottom-fixed foundations. Source: researchgate

Its potential in Europe

Economic advantages

What makes offshore wind a promising technology for the EU?First, it is an economically viable project with massive potential for expansion. There are five sea basins (North, Baltic, Mediterranean, and Black Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean) within the EU zone. Most offshore wind farms are currently in the North Sea: the four others areas remain relatively unexploited.

Secondly, offshore wind produces a high and steady capacity of energy compared to its onshore counterparts. Wind speeds are stronger and more consistent at sea, making offshore wind a less variable and weather-dependent RES.

Third, production costs of offshore wind have fallen dramatically in the past two decades. This is due to technological improvements that allow for the manufacturing of larger, more powerful and efficient turbines.

In the last five years, the production costs of wind energy reduced by 50% (WindEurope), and the levelised costs of electricity (LCOE) is due to decline by 40% by 2040. It is predicted that by 2030, offshore wind will be competitive with or even cheaper than fossil fuel-based technologies on global markets.

The EU as a global leader

Moreover, Europe is the global leader in offshore wind: it has the most offshore wind farms, and its technological, scientific and industrial experience is unparalleled. The EU leads in manufacturing of key components of wind farms, and almost half of wind industry companies are stationed in Europe – as are most leading research and development institutes.

The EU should not risk losing this competitiveness. The maintenance of its leadership in offshore wind will allow it to move towards energy autonomy and security. Given the EU’s current strong dependence on energy imports, this should not go unnoticed.

Meeting its policy goals

The EU plans to increase offshore wind energy production of 25GW to 60 GW by 2030, and 300GW by 2050. This plan is extremely ambitious. Even EU leaders in offshore wind, such as the Netherlands and Germany, are not set to meet their depollution targets by 2050. If their current policies continue as is, offshore wind capacity will reach 90GW by 2050 – significantly less than what the EU has planned.

So what does the EU need to meet these ambitious goals to exponentially expand this RES in the next decades? First, it needs money: to meet its 2050 target, the EU will need an investment of 800 billion euros, mainly through private funds.

Second, it needs more regional cooperation: there are huge disparities between countries. While Germany currently produces 7,505MW of wind power, France has only just started up its first offshore wind farm, producing 480 MW. Interconnection of funds, technology and expertise is essential to facilitate the growth of a Europe-wide industry.

The promise of “floating wind”

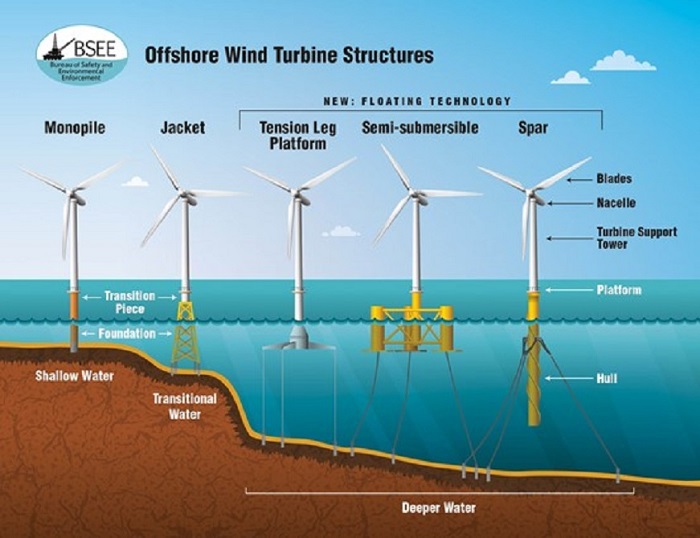

Third, the EU needs to keep investing in research and development, especially in floating turbines. Building bottom-fixed foundations is expensive and there are limits to the depths of the body of water in which they can be installed. Yet, to expand to 300GW, we need to build wind farms in deeper water.

Floating turbines offer a promising solution to this. Designed similar to an oil and gas platform, floating turbines are moored to the seabed with mooring lines and anchors. In this way, wind farms can be built much deeper into the sea.

Figure 4: Bottom-fixed vs. floating technologies. Source: equinor

Compared to bottom-fixed foundations, using this technology will lower the costs of materials (no need for seafloor foundations), maintenance (the turbine can be towed back to the shore) and production (turbines can be built on land, then towed to sea), and also reduce disturbance of marine life (usage of seafloor is minimal).

But promising as it sounds, floating wind is still on a pre-commercial level. With the current investment flow, it will only become profitable by 2030 (Equinor 2021). Until then, we will have to do with our current, less efficient, bottom-fixed technologies.

Conclusion

For myriad reasons, offshore wind presents an immense opportunity for the EU. Recognizing those opportunities, the EU has made big plans to expand its production capacity of offshore wind. But these plans are overly ambitious given the EU’s current investments in the industry. It’ll need more money, better interstate cooperation, and the capacity to build cheaper and further offshore. And while some promising solutions do exist on the horizon, they are not ready for commercial use just yet.

What do YOU think? Is offshore wind as promising as the EU makes it out to be? Let this be a starting point for your own research!