- India

- International

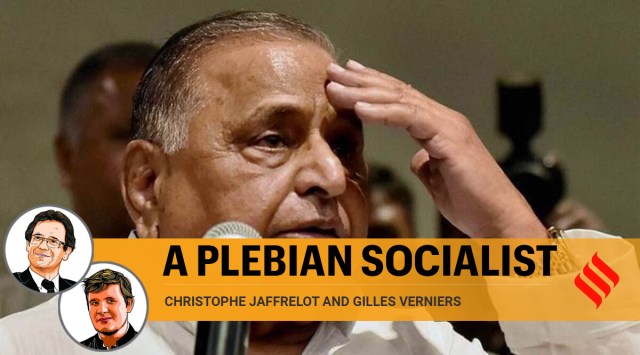

Mulayam Singh Yadav: A plebian socialist

Christophe Jaffrelot and Gilles Verniers write: Yadav played a role in national politics but the UP Vidhan Sabha was his political home, where he was elected 10 times.

Mulayam Singh Yadav played a key role in UP politics and, at times, in national politics, over a 45-year-long career.

Mulayam Singh Yadav played a key role in UP politics and, at times, in national politics, over a 45-year-long career.Mulayam Singh Yadav was one of the last heirs of the Lohiaite socialist tradition — if not the last one. This was a school of thought that did not believe in the Left’s Marxist class approach but sought to define a political ideology that corresponded to India’s brand of social and economic inequalities, rooted in caste, class, gender and language. Lohiaites promoted secularism, caste-based reservations and Hindi, a language which was supposed to help plebeians — who did not go to English medium schools — to access upward social mobility.

Lohia’s views on the intersectionality of these forms of inequalities translated into a recipe for political action that called for the unification of all subaltern groups, including Dalits, Muslims and Adivasis, into a social alliance and a political front. This strategy was particularly appealing to political leaders who came from their ranks.

Yadav had indeed true plebeian origins. Born in 1939 in an Ahir (Yadav) household in Saifai, a village in Etawah district, he was a promising wrestler before recycling his combativeness into politics, first as a student leader and then as a politician. He was attracted to Lohia because of his emphasis on equality and his promotion of caste-based positive discrimination. In 1966, at 27, he was the Chairman of the Reception Committee of the All India Yadav Mahasabha that held its annual conference in Etawah. The president of the organisation, then, was Rao Birendra Singh, the scion of the Rewari dynasty, a descendant of Rao Tula Ram and the future founder of the Haryana Vishal Party. This would be the beginning of Yadav’s connections with socialist leaders across the country.

One of the resolutions of the Subjects Committee asked for the implementation of the Kalelkar report (India’s first Backward Classes Commission). A year later, he contested and won in his mentor Nathu Singh’s constituency, Jaswantnagar, on a Samyukta Socialist Party ticket. Nathu Singh had identified Mulayam as a formidable organiser during his students’ politics days, and rapidly made him his political successor.

After Lohia’s death in 1967, he shifted to the Bharatiya Kranti Dal. Mulayam Singh Yadav was among the Yadav followers whom Charan Singh attracted to form the AJGAR coalition (Ahirs, Jats, Gujjars, Rajputs). According to Paul Brass, Yadav was specifically recruited to bring muscle into Charan Singh’s new party. He remained with Singh when he transformed the BKD into the Bharatiya Lok Dal, but kisan politics was not his cup of tea: He believed more in quota politics. During his first term as chief minister, between 1989 and 1990, he pushed for quotas, at a time when, by contrast, Jat leaders of his party, the Janata Dal, including Charan Singh’s protégé Devi Lal, opposed V P Singh’s decision to implement the Mandal Commission report.

When the Janata Dal imploded in 1991, Mulayam Singh Yadav returned to his original, socialist creed by creating the Samajwadi Party. And true to his Lohiaite plebeian inclination, he joined hands with the Bahujan Samaj Party. In 1993, the SP and the BSP formed a pre-election pact and then the government, enabling Yadav to be chief minister again.

The relations between the two partners, however, soon deteriorated. First, the BSP was getting worried about the recruitment of Yadavs in large numbers in the police and the state apparatus at large. Second, the Yadavs and other OBCs, who were anxious to improve their social status and to keep the most subaltern groups under their domination, reacted violently to the Dalits’ efforts towards social mobility.

Conflicts about the wages of agricultural labourers and disputes regarding land ownership had become more frequent since both groups — the Dalit and the OBCs — had become more assertive. These bones of contention partly explained the increasing number of “atrocities” perpetrated against Dalits. For Kanshi Ram, the rising graph of these atrocities was the main reason for the divorce from the SP. In 1995, this clash became more personal after the BSP accused SP cadres of physically attacking Mayawati during the infamous UP guest house incident. In reality, neither Yadav nor Mayawati could agree on the rotation of the CM’s position, a key part of their 1993 agreement.

Having lost his ally in 1995, Yadav had to step down as CM. Rather than seeking to build Charan Singh’s dream alliance of backward castes, he focused on consolidating support among Yadavs and Muslims. During his first tenure as CM, he gained many Muslims’ trust and respect by protecting the Babri Masjid, authorising the police to use lethal force against kar sevaks, earning Yadav the nickname “Maulana Mulayam”.

The support of his caste group and a minority representing one-fifth of the voters helped Yadav to become CM of UP for the third time in 2003. Before that, he had briefly played a role in national politics, as a member of the United Front’s cabinet. He served as Union defence minister between 1996 and 1998 and was elected three times in a row to the Lok Sabha from 1996 to 2003 (he would serve three more terms as MP). But the UP Vidhan Sabha was his political home. He was elected 10 times, losing only one election in 1980.

Mulayam Singh Yadav played a key role in UP politics and, at times, in national politics, over a 45-year-long career, before he handed the reins of SP to his son Akhilesh in 2012. Yadav’s relationship with Akhilesh became somewhat strained as the latter sought to build his own persona, outside his father’s shadow. But the new leader of the Yadav Parivar will keep the family tradition alive, and continue to root himself in regional politics, as attested by his recent decision to resign from the Lok Sabha to become Leader of the Opposition in UP.

Jaffrelot is senior research fellow at CERI-Sciences Po/CNRS, Paris, professor of Indian Politics and Sociology at King’s India Institute, London, and non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Verniers is Assistant Professor of Political Science, Ashoka University.

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

May 05: Latest News

- 0115 hours ago

- 0215 hours ago

- 035 hours ago

- 0416 hours ago

- 0516 hours ago