- India

- International

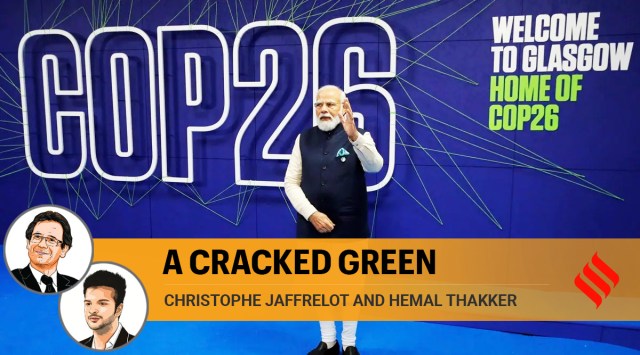

Why India’s green façade is cracking

Christophe Jaffrelot, Hemal Thakker write: Even though it has invested in renewable energy and announced a net-zero target, there is a gap between the announcements and the ground reality, as is evident from the promotion of coal.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the COP26 summit at the Scottish Event Campus (SEC) in Glasgow. (AP)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the COP26 summit at the Scottish Event Campus (SEC) in Glasgow. (AP)Last week at the COP 26 in Glasgow, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India has set a target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2070. India also updated its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) that have to be met by 2030. Its new pledge includes increasing the country’s installed renewable capacity to 500 GW, meeting 50 per cent of its energy requirements from non-fossil fuel sources, reducing carbon emissions by 1 billion tonnes and bringing down the carbon emissions intensity of the economy by 45 per cent from 2005 levels.

At the COP 21 in Paris, India, the third-largest emitter of carbon dioxide behind China and the US, made similar ambitious announcements and aimed to reduce the economy-wide emissions intensity by 33-35 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030. It also set a target of 40 per cent installed capacity from renewable energy resources and committed to creating a carbon sink of 2.5-3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, through additional forest and tree cover. Since then, India has made a name for itself globally because of its massive investments in solar energy. In August, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy announced that the country has installed 100 GW of renewable energy capacity. The majority of this 100 GW, about 78 per cent, is due to large-scale wind and solar power projects. While this is a milestone, India is on track to accomplishing only about two-thirds of its planned renewable target of 175 GW installation by 2022. To achieve its new goals, India will need to do more in different directions. For instance, it has a target of achieving 40 GW of green energy from the rooftop solar sector by 2022, but it has not been able to achieve even 20 per cent of that so far. In the transport sector, India has targeted a 30 per cent share of electric vehicles (EV) in new sales for 2030. However, according to the Climate Action Tracker, to be compatible with the Paris Agreement, the share of EV sales needs to be between 80-95 per cent by 2030, and 100 per cent by 2040.

India also needs to cut down subsidies to the fossil fuel industry drastically — not the case currently. While in the past seven years, the country has invested Rs 5.2 trillion in renewable energy, the investment in fossil fuel industry, though down by (only) 4 per cent from 2015-19, was Rs 245 trillion. Worse, coal production is estimated to increase to one billion tonnes by 2024 from 716 million tonnes in 2020-21. India is already home to the second-largest coal-fired power plant pipeline in the world. According to the Central Electricity Authority, coal capacity is projected to increase from 202GW in 2021 to 266GW by 2029-30.

The Government of India is not actively discouraging such investments. On the contrary, coal subsidies are still 35 per cent higher than the subsidies for renewables and coal-fired power generation receives indirect financial support from the government through income tax exemptions and land acquisition at a preferential rate. In June 2020, the government carried out an auction of 41 coal mining blocks in which private players were allowed to bid for the first time. India’s reliance on coal is the main reason for the country not embarking on a serious decarbonisation trajectory. The Climate Action Tracker, an independent scientific analysis that tracks government climate action against the Paris Agreement targets, deems India’s performance as “highly insufficient” simply because coal represents about 70 per cent of the country’s energy supply. According to a British Petroleum study, in 2040, coal will represent 48 per cent of the primary energy consumption of commercial fuels in India while renewable energy will contribute only 16 per cent. This means if the growth rate of the economy remains the same, the country’s carbon dioxide emissions will double to 5 Gt by 2040. India’s share of global emissions will increase from 7 per cent today to 14 per cent by 2040.

At the 2009 Copenhagen summit, India was part of a coalition of countries — including the other emerging economies and the US — which was not as interested as Europe (and a few others) in global warming mitigation. In 2015, however, India played a very constructive role, along with Europeans and others, during the COP 21 in Paris. Prime Minister Modi and then French President Francois Hollande initiated a Solar Alliance that was intended to help poor countries to invest in this renewable energy. Since then, New Delhi has acquired a green image, and Western, as well as Indian observers, have talked about PM Modi as a potential global climate leader, capable of setting the agenda on climate-related issues, while also reminding the developed countries that treating nature well comes naturally to Indians.

India’s green façade now seems to be cracking. Even though New Delhi has invested in renewable energy and announced a net-zero target, there is a gap between the announcements and the ground reality, as is evident from the promotion of coal. Indian officials argue that Western countries are historically responsible for climate change, India’s per capita emissions remain very low, growth is the country’s priority, and that the rich countries are not spending the $100 billion they committed at COP 21 to helping the decarbonisation strategies of poor countries (last year only $ 80 billion were spent). All this is indeed true, and the rich countries need to financially support the global south. However, it is also true that India’s energy transition would be in its own interest because, otherwise, economic growth will not be sustainable and human security will be at stake if dozens of millions of climate refugees are created due to the devastating consequences of climate change.

This column first appeared in the print edition on November 11, 2021 under the title ‘A cracked green’. Jaffrelot is senior research fellow at CERI-Sciences Po/CNRS, Paris. Thakker is food and agriculture policy analyst and student of environment policy at the Paris School of International Affairs, Sciences Po

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 29: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05