One must wait until the seventeenth century to see art become no longer just the object of isolated exchanges carried out in order to enlarge the coffers of churches and princes and to give itself out as a commodity to institutions capable of ensuring aboveboard transactions that would allow price comparison and therefore competition among buyers. Even if the existence of a first auction in Venice as early as 1506 is known, such institutions grew in number in the Netherlands and the system of transactions was set in place at that time, then in London and in Paris, which starting in the eighteenth century became a stronghold where objects of all provenances were traded. Still, very few sales at auction were organized until 1730, then once a month in the 1760s, and already almost once a week by the 1780s.

As regards galleries, Watteau has bequeathed to us the famous sign of Gersaint, which exhibited, all at once, pictures, sculptures, and objects of natural history. One witnessed the emergence of the figure of the dealer, who was often trained as a painter or engraver, therefore an expert, both an artist and a retailer–which is not surprising to connoisseurs of the nineteenth century. Jérôme Poggi offers us, in this regard, some new sources of interest. His unique study of the “anterooms of modernity” under the Second Empire shows us the metamorphoses of the art world and of its market–which, as we knew, fed on the decay of the Salon system but not to this point of wavering between two opposed models. The most audacious experiments in new commercial methods were undertaken by artists themselves and were based at the time upon a rather lively resistance to commercialization. Such experiments were born at the very origin of the modern market and naturally drew upon the utopias of the generation of the Revolution of 1848.

Descended from the Saint-Simonians and the Fourierists, Louis Martinet distinguished himself along these lines by allowing the great artists of the day to be seen rather than to be bought. Among those artists were Ingres, Manet, Delacroix, Corot, Rousseau, Millet, Courbet, and Carpeaux. He imagined the possibility of reuniting all the arts in one gallery that would also be a lively meeting area, a boudoir, and a concert hall. He failed, if you will, like the revolutionaries whose projects, not alien to these antecedents, would also fail in the future–particularly in France in the 1960s. He had to abandon his project, but the idea was not, for all that, thereby exhausted, nor had the broadly shared feeling disappeared that art is not a commodity like any other but, rather, an original object worthy of its own system of exchange.

Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux engages in a dialogue with Jérôme Poggi. As a fine connoisseur of the cultural economy, he sheds light on the present-day crisis of the traditional models. Amidst this crisis, we see reborn the debates and experiments from the nineteenth century with a desire to get things moving that, in his view, is not unlike the passion for reform under the Second Empire.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of January 19th 2006

Painting to be seen

versus Painting to be sold:

The Paying Exhibition as Alternative to the Commercialization of the Work of Art under the Second Empire

Jérôme Poggi

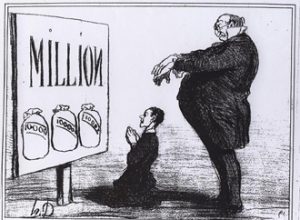

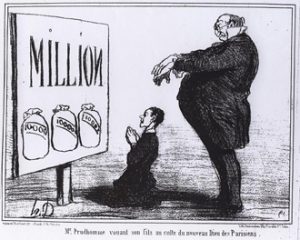

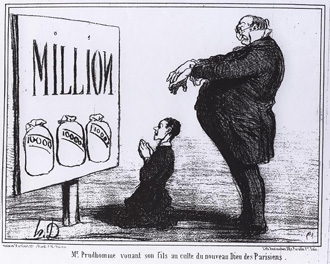

Honoré Daumier, “Monsieur Prudhomme dedicating his son to the worship of the Parisians’ new God, Le Charivari, February 2, 1857.

The Second Empire marks the French economy’s entrance into its second industrial revolution. Brought on by a thoroughgoing reform of the financial tools entrepreneurs had at their disposal for investment, this metamorphosis was accompanied by an unprecedented movement of capitalization and by an exceptional boom in the stock market. As Alexandre Dumas fils wrote, the French Bourse was to the Second Empire what “the cathedral was to the Middle Ages,” dedicated to a new God of whom Parisians were the fervent worshipers. This financial fever quickly caught hold of the art market, which, barely recovered from the serious economic crisis it had undergone during the Second Republic, became in turn a “speculator’s Eldorado.”[ref]Philippe Burty, “L’Hôtel des ventes et le commerce des tableaux,” Paris Guide par les principaux écrivains et artistes de la France (Paris: Librairie internationale, 1867), vol. 2, La Vie, p. 953.[/ref] “One no longer gathers a collection in order to have it, to enjoy it . . . but in order to sell it and to make some money off of it,” as the critic Paul Lacroix complained in 1861.[ref]Anatole de Montaiglon, “L’art et les artistes en 1860,” Annuaire des artistes et des amateurs (Paris, 1861), p.72.[/ref] The work of art was no longer anything but a commodity, a good investment, whose exchange value triumphed over its use value, the literary critic Émile Montégut worried in the Revue des Deux Mondes : “We have yet to calculate what disorders occur in public taste and in the general intelligence of a society when there no longer exists any proportionality between the intrinsic value and the commercial value of art objects.”[ref]Émile Montégut, “De quelques erreurs du goût contemporain en matière d’art,” Revue des Deux Mondes, July 1, 1861.[/ref] In turn, the Salon of Living Artists was beginning to look more and more like a “frame fair,” lining up works like so many commodities for sale. Its presentation in the French Palace of Industry built for the Universal Exhibition of 1855, and no longer in a palace of fine arts worthy of that name, was perceived as “a sort of deadly omen, a fatal sign of the successful preeminence of industry over art.”[ref]A. J. Du Pays, “Exposition des ouvrages des artistes vivants au Palais de l’Industrie,” L’Illustration, June 20 1857, p. 387.[/ref] While some critics resigned themselves to speaking “the language of [their] time : debit and credit–product and consumption,”[ref]L. Saint-François, “L’exposition permanente,” l’Artiste, June 1, 1860. pp. 221-22.[/ref] others militated in favor “of an anti-stock-exchange movement” that “alone can . . . save the little bit of literature and journalism properly speaking that . . . still remains.”[ref]Arnould Fremy, “Un mouvement anti-boursier,” Le Charivari, January 8, 1857.[/ref]

“Owning is Nothing, Enjoyment is Everything”[ref]Stendhal, De l’amour (Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1967), p. 122.[/ref]

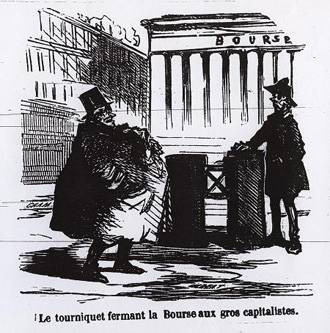

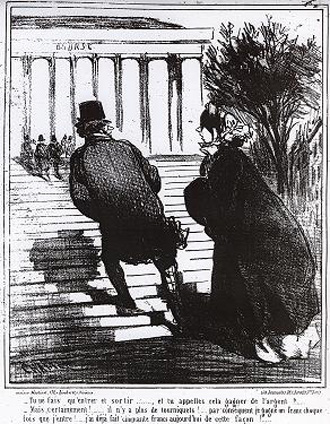

Cham, “The turnstile closing the stock market to the big capitalists,” Le Charivari, January 4, 1857.

Numerous initiatives answered to this call at the start of the 1860s to oppose the commercialization of art, the fetishization of the work, and the artist’s exploitation on the market. [ref]The decorative and industrial forms of art were at this same time being encouraged as alternatives to the singularity of the original work of art.[/ref] In reaction to the consumerism that was then transforming Western culture, a certain form of Romanticism in the experience of art had a resurgence that privileged the use value of works in the Stendhalian spirit of “enjoyment of the beautiful.” Some cultural practices that had pretty much disappeared since the fall of the July Monarchy were then making a resurgence in cultivated society, such as the performance of tableaux vivants and the renting out of art works. But it was above all through paying exhibitions that some were going to seek to emancipate the work from its commodity-based logic by championing it as a work to be seen and no longer as a work to be sold. While entry to museums in France was going to remain free of charge until 1922, the idea of making people pay for access to exhibitions became predominant starting in 1857, the date when the Salon des Artistes definitively became a paying exhibition. The idea of making people pay for the use of an object rather than for the object itself was presented at the time as an alternative to the market economy, and it spread rather symptomatically throughout society as an illustration of the scruples society was feeling about converting over to a pure market economy. It was not up to the Bourse which did not give in to this use-based economy. During this same year of 1857, paying turnstiles [tourniquets payants] were installed at the entrance to the stock-market building in order to limit the flow of curiosity-seekers who came there as one went to a show and in order to contain the speculative contagion that was ruining poor people who were caught up in the hunt for easy money. A critic ironically observed that “the modern financial system is bound to be reformed by the turnstile.”[ref]Clément Caraguel, “Péages et tourniquets,” Le Charivari, January 6, 1857.[/ref]

“Pay Per View”

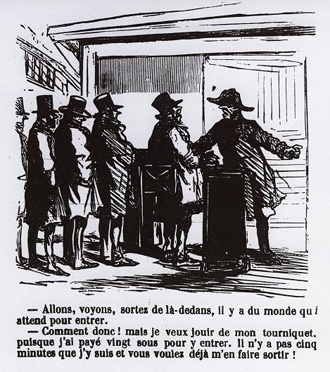

–Get going, come on now, get out of there, there’s a lot of people waiting to get in. –How’s that? But I want to enjoy my turnstile, since I paid twenty cents to get in. I’ve only been here five minutes and you want me to leave already! Cham, “A walk in the salon,” Le Charivari, May 15, 1859.

The idea of making one “pay to see” or “pay per view” was, however, not entirely new. In 1799, Jacques-Louis David was the first to experiment with this idea when he exhibited his Sabine Women in a room at the Louvre. David was inspired by the lucrative English model of paying exhibitions. Wishing to give to the arts the means to “enjoy a noble independence of mind,”[ref]Jacques-Louis David, Le tableau des Sabines, suivi de Note sur la nudité de mes héros (La Rochelle: Rumeurs des Ages, 1997), pp. 7-17.[/ref] he claimed then the power to offer to the public’s view a work that, without this, would become “the conquest of a rich man” who, jealous of “his exclusive property,” would prevent the rest of society from seeing it. The ambition of such an experiment, which was as economic as it was social, was nevertheless ill perceived by the critics. The latter firmly condemned the “sordid venality” of the numerous artists who imitated David. Painters then abandoned the idea of being remunerated by the showing of their labor and limited themselves to being a part of a market economy subject to sales and orders.

The principle behind the paying exhibition did not disappear for all that. Exhibitions of painting organized for charitable ends gradually accustomed “the public to pay to see painting,”[ref]Delacroix to Soulier, April 21, 1826, Correspondance générale d’Eugène Delacroix (Paris, 1936), vol. 1, pp. 178-179, quoted by Jon Whiteley, “Exhibitions of Contemporary Painting in London and Paris 1760-1860,” Saloni, Gallerie, musei loro influenza sullo sviluppo dell’arte dei secoli XIX e XX (Acts of the Twenty-Fourth International Art History Congress, Bologna), September 1979.[/ref] especially after 1846 when Baron Taylor’s association of painters, sculptors, engravers, and architects inaugurated a series of paying exhibitions in the galleries of the Bazar Bonne-Nouvelle in order to fill its relief coffers. This pecuniary principle was soon going to be picked up by the French Government, which, little by little, made people pay for access to the Salon. It was under the Second Republic, and principally for budgetary reasons tied to the economic crisis, that a first paying day was instituted. Soon there would be two of them, in 1852, three in 1853, and finally six in 1855 for the Universal Exhibition,[ref]See Patricia Mainardi, Art and Politics of the Second Empire (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989), pp. 44-46.[/ref] after which time this measure became the rule. In none of these instances was it a matter of paying back directly and equitably to the artists a portion of the proceeds collected on the exhibition of their work. On the contrary, starting in 1857 the Government decided to devote the full take from admissions to the acquisition of works exhibited at the Salon, a measure designed to enrich the national collections and to encourage the market in art. Gustave Courbet was the first to champion the rights that artists might expect from these new arrangements.

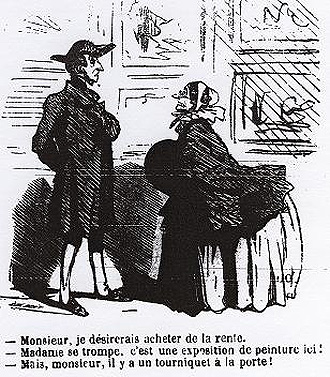

–Sir, I’d like to buy some stock. –Madame is mistaken, this is an art exhibition here! –But sir, there’s a turnstile at the door! Cham, “A walk in the salon,” Le Charivari, May 15, 1859.

As early as 1853, he demanded from the Government a portion of the proceeds from the Exhibition, thinking that it was in the main his pictures that had attracted visitors to the Salon and had given rise to the most reviews in the Press.[ref]“I reminded him also that he owed me 15,000 francs for the entrance fees they had collected with my pictures from previous exhibitions, that the employees had assured me that individually they had brought in 200 people a day to stand in front of my Bathers. To which he responded with the following assinity: that these people did not go in in order to admire this painting. It was easy for me to respond, in objecting to his personal opinion and telling him that the question did not lie there, that whether for criticism or for admiration, the truth was that they had received the entrance fees and that half of the reviews concerned my pictures” (Gustave Courbet to Alfred Bruyas, October [?] 1853, Correspondance de Courbet, ed. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu (Paris: Flammarion, 1996), pp. 107-09.[/ref] Two years later, at the margins of the Universal Exhibition, he retried David’s experiment from a half century earlier when presenting a retrospective exhibition of his work that the public was invited to visit for a franc a head. The success of this show, in which the pictures were as much for sale as to be seen, was nevertheless more critical than financial, thus leaving Courbet skeptical about the idea of a paying exhibition. Instead, he preferred a more complex commercial strategy, both market-oriented and media-conscious.

Louis Martinet and the French National Society of the Fine Arts (1862-1865)

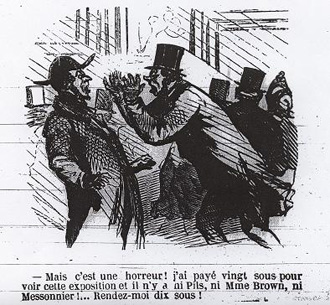

–But that’s awful! I paid twenty cents to see this exhibition and neither Pils nor Madame Brown nor Messonnier is here! . . . Give me back ten cents! “The 1863 Exhibition photographed by Cham,” Le Charivari, May 10, 1863.

It was only at the turn of the 1860s that the principle of the paying exhibition was really tested by the artist Louis Martinet (1814-1895). who had the idea of offering artists an alternative to a more and more prescriptive art market. Of a Romantic cast of mind, this former student of Baron Gros occupied an ideal position in order to observe the evolution of the art milieu after the Revolution of 1848. A member of the team of inspectors in charge of organizing the Salon of Living Artists beginning in 1849, he was a privileged witness to the institutional, economic, and social reforms briefly tested during the Second Republic. Ousted from a fine-arts administration that had become more and more sectarian starting in 1855, he then became aware of the impasse in which artists found themselves, caught as they were between an academic system in complete decay and a purely speculative market still incapable of supporting artistic creation. Turning toward Baron Taylor’s association, he encouraged the latter to organize exhibitions, notably the retrospective one of the work of Ary Scheffer presented in 1859 in the galleries built for the occasion in the gardens of the Marquis of Hertford, on 26 Boulevard des Italiens. This was the place with which Martinet, then nearly fifty years old, was going to associate his name by opening there a “permanent exhibition” that would welcome until 1865 all the main artists of the nineteenth century, from Ingres to Manet, passing by way of Delacroix, Corot, Rousseau, Millet, Courbet, Whistler, Puvis de Chavannes, Carpeaux, and so on. Making the most of the new liberal winds blowing through the Empire starting in 1860, this Republican in his head and Orleanist in his heart whose ideas, like some of his friendships, brought him close to Saint-Simonian circles was going to use this location to try to invent a new form of commerce between artists and society. The inspiration was decidedly Romantic.

His primary ambition when he inaugurated his exhibition in February 1861 was “to teach artists to do business themselves,”[ref]Introduction to the Catalogue of the Exhibition of the French National Society of the Fine Arts (Paris: Impr. J. Claye, February 1864).[/ref] leaving to the State the responsibility to decorate public monuments and support major painting efforts. Adopting very liberal, free-market, even industrialist points of view,[ref]“Let the State, abdicating to the benefit of industry, leave to the business enterprise alone the right to spread art,” Henri Boisseaux wrote in the Courrier artistique, “Étude sur la situation des compositeurs français (deuxième article),” Le Courrier artistique, February 1, 1863.[/ref] Martinet was at the same time a fierce opponent of the market’s exploitation of the artist. Whereas it “always seemed [to him] that the words art and speculation were mortal enemies,”[ref]Louis Martinet, “L’exposition permanente du Boulevard des Italiens,” Le Courrier artistique, August 1, 1861.[/ref] he intended “to be the first private enterprise in France to be able, with absolute independence, to serve gratis as an intermediary between artists and amateurs.”[ref]Louis Martinet, “Aux artistes et aux amateurs,” Le Courrier artistique, June 15, 1861.[/ref] As Edmond About wrote, it was a matter of creating a “market of a new kind”[ref]Edmond About, Le Courrier artistique, July 1, 1861.[/ref] in which the producer and the buyer would be able to deal with each other through an administrative intermediary. The latter would obtain no right to exhibit the work in question nor would he collect any commission, as posted in the regulations of the permanent exhibition, which limited its resources to the payment each visitor made upon entering.

Royalties in Painting

–You’re just going in and out . . . and you call that making money? –But of course! . . . No more turnstiles! . . . Consequently, I earn a franc every time I enter! . . . I’ve already made fifty francs today in this way! . . . Cham, “You’re just going in and out . . . and you call that making money? . . . ,” Le Charivari, December 2, 1862.

This liberal, free-market conception of Martinet’s business enterprise was to take a still more radical turn as the debate on royalties [le droit d’auteur] again took front stage in France. In the extension of the Brussels International Congress of 1858 devoted to the question of artistic property, a new congress, as reported with great interest by the Courrier artistique, was organized during the international exhibition at Antwerp during the Summer of 1861. Shortly thereafter, in January 1862, the French Government created a national commission charged with reflecting upon the improvements to be made in property-rights legislation. Martinet, like the artistic class as a whole, took part in this reflection in his review. He opted for the very liberal, free-market ideas expressed by Jules Hetzel, publishing excerpts from Hetzel’s writings that recognized the right of artists, or their beneficiaries, to retain ownership of the work in perpetuity. His ardor in the defense of this point of view led him to the idea, “so simple and so natural that it should have been expressed long ago,”[ref]Louis Martinet, “Des droits d’auteurs en peinture,” Le Courrier artistique, February15, 1862.[/ref] of remunerating artists through royalties, as writers and composers are. This discovery coincided with a trip to England in which he participated as member of the French Commission for the Universal Exhibition of 1862. Very impressed by the power of the principle of association long practiced by the English people, particularly within their Art Unions, he realized how much, “in the arts especially, the spirit of association can change everything.”[ref]Louis Martinet, “De l’association dans les arts,” Le Courrier artistique, December 1, 1861. We know the impact the discovery of Trade Unions had on the French labor and workers’ movement during this Exhibition. Without making Martinet into the Henry Tolain of the art world, it is fitting to underscore the importance the discovery of Art Unions (private societies of amateurs who organized exhibitions and lotteries) had for the development of his business enterprise. He makes several references to these Art Unions.[/ref]

It was therefore with the aid of the law of association, “which has been eternal since the time of the family . . . until that of the nation,”[ref]Louis Martinet, “De l’association dans les arts II,” Le Courrier artistique, December 1, 1862.[/ref] that Martinet was going to try to invent a new art economy that would federate artists within a French National Society of the Fine Arts. Its “principle is that of royalties in painting–the legitimate and equitable profit the artist should be able to draw from the exhibition of his work.”[ref]Louis Martinet, Le Courrier artistique, March 15, 1862.[/ref] Created in the Spring of 1862, the Society was presided over by Théophile Gautier and quickly rallied nearly two-hundred artists who would then be joined by about fifty amateur members. His principal goal was to organize an annual exhibition of previously unseen works from the members, to tour this exhibition in various French départements and abroad, and to share whatever profits were made.

One publiciste after another appeared in the columns of the Courrier artistique to defend the idea of a business enterprise that would not be afraid of being accused of “utopianism,” as P.-C. Parent wrote, stating that it could very well be “the fortune of the Society.”[ref]P.-C. Parent, “La Société nationale des Beaux-arts,” Le Courrier artistique, December 6, 1863.[/ref] It was Francisque Sarcey, the famous publiciste of Opinion nationale, a daily whose Saint-Simonian sympathies were well established, who delivered the longest and most vigorous defense of the French National Society of the Fine Arts’ project. In his view, “the painters are still in the bad old days of 1788. They make a picture, sell it, and make another one, and so on and so forth. Not one of them has imagined that he could do so without alienating ownership of his picture, thereby drawing an annual income.” [ref]Francisque Sarcey, “Petite chronique,” Le Courrier artistique, February 14, 1864.[/ref] He then enjoined the artist to make his own revolution and to address himself in the following way “to the thousands of men who make up the public”: “I have just completed a work; you claim that your eyes delight in it; so be it, but I deduct a certain amount for your curiosity. My picture is a form of capital; I have the right to expect a certain income therefrom, without for all that being obliged to divest myself of the capital. I want to enter into the spirit of the new society, which is democratic, and to carry out, to my benefit, the revolution writers and composers, as far as they are concerned, have already made.”[ref]Francisque Sarcey, “Petite chronique,” Le Courrier artistique, February 28, 1864.[/ref]

For Sarcey, it was a matter of “harmonizing with the democratic form of our society the industrial conditions of painting and sculpture,” and “it is the association alone, the ultimate form of democracy, that can democratize art.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

The Salon intime

The project defended by the French National Society of the Fine Arts went well beyond a simple reform of the status of the artist, for it also aspired to effect a social reform of art. But the “democratization of art,” as understood by Sarcey, had nothing to do with the one that Courbet was defending at the same time in a manifesto published on the occasion of the Antwerp Congress of 1861.[ref]There, Courbet declared that “realism is, by essence, the democratic art” (quoted by Marie-Thérèse de Forges, in Gustave Courbet [Paris: Éditions des musées nationaux, 1977], p. 36).[/ref] The ideology defended on the Boulevard des Italiens was not aesthetic but, rather, economic. By 1861, democracy had long ago made its entrance onto the artistic scene. The Salon had become “a veritable Babel of art [wherein] all languages, all styles, all techniques . . . were thrown together and collided against each other”; this was the triumph of an individualism “in which everyone [no longer] depended upon anyone but himself.”[ref]E.D. Dupays, L’illustration, May 11, 1861.[/ref]

It was against this individualism that Martinet’s willfully eclectic project stood up. In his view, his salons were to constitute in the proper sense of the term a society–an artistic club as it was called by Sarcey, who saw therein a form of democratic resurgence of the aristocratic salons of old. One only had to pay one’s dues in order to join a community of artists and amateurs who were intent on sharing, during the course of “intimate evenings,” a collective experience of art. Gautier went so far as to propose imitating the habits of the “Fridayans,” an artistic community he had discovered in Saint Petersburg that met on Friday evenings to paint or draw collectively around a table and then sell these works for the benefit of their society.

Martinet never let up in his efforts to make his gallery convivial, transforming it into a hall capable of accommodating concerts, equipping it with boudoirs, smoking rooms, a lecture hall, and a billiard room. Critics poked fun and asked if one day there might not be a bit of cooking thrown in there, too. This was also the reproach of some painter members, like Théodore Rousseau, who took a dim view of this multidisciplinary drift :

Last year, I told Martinet that he would end up making us run a café, and it seems to me that we’ve reached that point. Here we have painting with music and hot toddies. We will have dancing and flowers; perhaps we will be able to inscribe on our banner: “Here the five senses are enchanted.”[ref]Letter from Théodore Rousseau to Théophile Gautier, Feburary 3, 1864. Correspondence of Théodore Rousseau, BSb22L121, Department of Graphic Arts, Louvre Museum, Paris.[/ref]

And yet that was what Martinet had in mind: to appeal to the senses, to stimulate their connections, and to achieve in the end a sort of Romantic totality on the level of feeling or sentiment. This was the ultimately avowed goal of the concerts organized in the exhibition rooms, whose ambition was to arrive at the fusion of these two arts that are so well made to cohabit. . . . Look at a Corot, for example, while listening to a Mendelssohn elegy, and the painter will no longer be a mystery to you. Thus would Diaz be complemented by Monpou, Delacroix by Berlioz, Marilhat by Félicien David, Raphael by Mozart, Michelangelo by Beethoven, and so on.[ref]Le Courrier Artistique, April 15, 1863, p. 4.[/ref]

The preponderant place given to sentiment in Martinet’s project follows logically from the principle of the paying exhibition in that the exhibition space itself becomes the site of artistic experience. The exhibition takes on the value of a work. Critics at the time readily compared the art of hanging an exhibition to that of the jeweler who needs to know how to use “the law of contrasts”[ref]R. de Mercy, “Quelques observations sur les expositions officielles,” Le Courrier artistique, February 15, 1863.[/ref] in order to set precious stones together to the best effect. It was to this end that Martinet applied himself, with a view of decoration that was opposed in this respect to the utilitarian logic presiding over the hanging of paintings in Parisian museums and at the Salon of Living Artists, the later having ended up hanging artists alphabetically. His “intimate Salon,” as Zacharie Astruc called it,[ref]Zacharie Astruc, Le Salon intime (Paris: Poulet-Malassis, 1860).[/ref] “in which no canvas made one blink or drew one’s eye,” “undeniably [bore] the cachet of a harmony that was as soothing as it was powerful, grabbing hold of the spectator with an impression of reverence.”[ref]Albert de la Fizelière, “Exposition de tableaux modernes tirés de collections d’amateurs,” L’Artiste, March 1, 1860.[/ref]

In Dressing Gown and Slippers

As sensible as it might seem, Martinet’s business undertaking was a resounding failure that latest only a few months. As he would himself write to the Count of Nieuwerkerke, he had launched himself into a “purely artistic work” and not an “industrial” one.[ref]Rapport de Louis Martinet au comte de Nieuwerkerke, October 14, 1864, Z61, French National Society of the Fine Arts, French National Museums Archives, Paris.[/ref] The project of paying exhibitions quickly fell through when faced with the individualism of member-artists who did not respect their promises to send a previously unseen work to the show. The Society’s economic fragility obliged Martinet to continue to sell works even while he invented the most tortuous lottery mechanisms possible to avoid this inevitability. But at this time near the end of the Second Empire, it was utopian to seek to escape from the overall economy of an increasingly capitalist society that was fetishizing the commodity idea as denounced by Marx in Capital. The fate of the turnstiles at the Brongniart Palace (the Bourse) offers edifying testimony of this state of affairs. Their existence did not last any longer than the exhibition galleries on the Boulevard des Italiens. Eliminated by the French Government on January 1, 1862, they were repurchased at a modest price by their manufacturer who “counted on carving them up into little fetishes to be worn as bracelets [that] stock traders, who are naturally superstitious, will pay for . . . at a good price,” as Le Charivari reported in a farcical tone.[ref] Castorine, “La semaine de la Bourse,” Le Charivari, February 17, 1862.[/ref] At the end of the Second Empire, the desire for an intimate relationship with a work became such that it necessarily had to pass by way of a form of appropriation, whether it was a matter of the original or of its reproduction. As Walter Benjamin wrote, “the domestic realm becomes the true asylum of art” in the nineteenth century, and it is in this space “that it falls to the collector to undertake the Sisyphean task of removing from things, because he possesses them, their commodity character.”[ref]Walter Benjamin, Paris, capitale du XIXème siècle (Paris: Editions Allia, 2003), p. 26.[/ref] As testimony to this, let us listen to a visitor to an exhibition of painting similar to the one on the Boulevard des Italiens, organized in conjunction with the Circle of the Rue de Choiseul. Seduced at first by the “carefully prepared temperature,” the thick carpets, the deep sofas, and the exquisitely hung works, the visitor finds himself dreaming of “dispossessing these gentlemen of the Circle and of appropriating everything for himself, the gallery and the outlying buildings, the carpets, manservants, and pictures.” A bit further on, he continues by confiding to the reader that he “does indeed find, and this may be said without joking, that it is impossible to have absolute enjoyment of a picture unless it belongs to you, at least to live in its company, to see it from all its angles and at each hour of the day. Each canvas demands a sort of apprenticeship, an initiation that can occur only in the silence of one’s home, in dressing gown and slippers.”[ref]“L’Exposition de tableaux du cercle de la rue de Choiseul,” La vie parisienne, January 1864, pp. 124-26.[/ref]

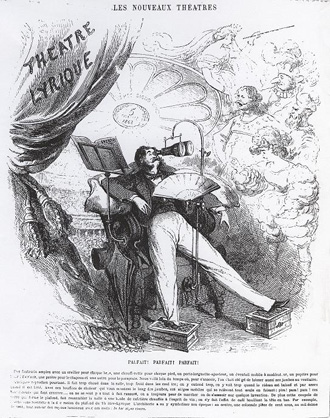

Despite the comfort, refinement, and friendly atmosphere offered by the galleries on the Boulevard des Italiens, the public of the Second Empire was not ready to “pay to view” exhibitions of modern art that it could henceforth visit for free on the premisses of art dealers like Goupil or Durand-Ruel–who, in turn, began to organize “intimate exhibitions” of their own following the model of the paying exhibitions. If one is going to pay to live through a sense-filled experience, it is strong sensations and the most lively emotions that the public will seek out in exchange for a few coins. Even more than the modern art galleries, it was ultimately places of entertainment and distraction that were to be the Boulevard des Italiens’ main competitors. Whether it was a matter of panoramas, theaters, or other types of opera, which underwent a considerable degree of development at the end of the Second Empire, the “paying spectacle” was ultimately going to win out over the “paying exhibition.” The public’s five senses were much more intensely enchanted there than in Martinet’s galleries. In the 1860s, while Charles Garnier was pursuing the construction of his new opera house a few meters away from the Boulevard des Italiens, the public’s comfort was becoming a major preoccupation for all theater managers. For, it was the public that was paying ; it was its opinion that thenceforth prevailed in the construction of new halls, as against that of the architects. This form of “clientelism,” which is subject to the pleasure of the spectator, expressed the simultaneous emergence of the market economy and the leisure society. This is the meaning of an 1863 cartoon illustrating the modern comforts found in the new theaters, which thenceforth offered to the public “ample seating with a pillow for each arm, a warmer for each foot, an adjustable opera-glass holder, a movable multispeed fan, a stand to lay down one’s copy of L’Entracte, a peg for one’s hat, and another for one’s umbrella.” But that is a comfort that is coined, as the image’s caption underscores in conclusion : “Let us praise the Lyric Theater’s ceiling decoration : the architect knew how to symbolize thereon his era : in the center, an enormous hundred cent coin, dated 1862, completely surrounded by rays of light with the following words : In Hoc Signo Vinces.” In this sign you shall conquer. . . . It is this financial and public triumph that was to await Louis Martinet when, after having closed his exhibition in 1865, he transformed his gallery to make it into a Theater of Parisian Fantasias. [ref]“THE ARCHITECTS: Really, the public is too educated; now it gives the orders. It’s a shame, we’ve never seen that before. THE PUBLIC (to itself while leaving): Since I’m the one who pays, I really have the right to voice my opinion” (in J. Denizet, “A propos des salles de spectacles,” Le Charivari, March 11, 1862).[/ref]

Bibliography

ALTICK, Richard. The Shows of London. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978.

BAETENS, Jan. Ed. Le combat du droit d’auteur. Anthologie historique. Paris: Les Impressions nouvelles, 2001.

BENJAMIN, Walter. Paris, Capitale du XIXème siècle. Paris: Éditions. Allia, 2003.

CHAUDONNERET, Marie-Claude. L’Etat et les artistes, de la Restauration à la monarchie de Juillet (1815-1833). Paris: Flammarion, 1999.

COURBET, Gustave. Correspondance de Courbet. Petra Ten-Doesschate Chu. Ed. Paris: Flammarion, 1996.

DAVID, Jacques-Louis. Le tableau des Sabines. La Rochelle: Rumeurs des âges, 1997.

FOUCART, Bruno. Ed. Le Baron Taylor, l’association des artistes et l’exposition du Bazar Bonne-Nouvelle en 1846. Paris: Association des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, architectes, graveurs et dessinateurs, 1995.

GAILLARD, Chantal. Proudhon et la propriété, Les travaux de l’atelier Proudhon. Paris: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 1988.

GIBAUD, Bernard. Aux sources de la mutualité 1789-1989. Paris: Éditions FNMF, 1989.

JENSEN, Robert. Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

KALIFA, Dominique. “L’ère de la culture marchandise.” Revue d’histoire du XIXème siècle (Aspect de la production culturelle au XIXème siècle), 19 (1999).

KRACAUER, Siegfried. Jacques Offenbach ou le secret du Second Empire. Paris: Gallimard, 1994.

MAINARDI, Patricia. Art and Politics. The Universal Exhibitions of 1855 and 1867. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

– “Courbet’s Exhibitionism. » Gazette des Beaux-arts, 2 (1991): 253-266.

– “The Double Exhibition in Nineteenth-Century France.” Art Journal, 1 (1989).

MCWILLIAM, Neil. Dreams of Happiness: Social Art and the French Left 1830-1850. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

MCCAULEY, Elizabeth Anne. Industrial Madness: Commercial Photography in Paris, 1848-1871. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994.

POULOT, Dominique. Musée, nation, patrimoine 1789-1815. Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

PICON, Antoine. Les saint-simoniens, Raison, imaginaire et utopie. Paris: Belin, 2002.

PROUDHON, Pierre-Joseph. Du principe de l’art et de sa destination sociale. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002.

– Les majorats littéraires. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002.

ROSANVALLON, Pierre. Le libéralisme économique. Histoire de l’idée de marché. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1989.

SENNETT, Richard. The Fall of Public Man. New York and London: W. W. Norton, 1996 (1976).

RUBIN, James Henry. Realism and Social Vision in Courbet & Proudhon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

– Une fraternité dans l’histoire. Les artistes et la franc-maçonnerie aux XVIIème et XIXème siècles. Paris: Édtions Somogy, 2005.

WHITELEY, Jon. “Exhibitions of Contemporary Painting in London and Paris, 1760-1860.” Saloni, Gallerie, Musei e Loro Influenza sullo Suiluppo dell’Arte dei Secoli XIX e XX (Acts of the Twenty-Fourth International Art History Congress, Bologna), September 1979. Pp. 69-87.

WILLIAMS, Rosalind H. Dream Worlds: Mass Consumption in Late Nineteenth-Century France. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1982.

WOODMANSEE, Martha. The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

ZUTTER, Jorg. Ed. Courbet, artiste et promoteur de son œuvre. Exhibition Catalogue, Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland. Paris: Flammarion, 1998.

Jérôme Poggi After having worked for several years in the institutional world of contemporary art, in particular at the Kerguéhennec estate where he was deputy director, Jérôme Poggi today has committed himself to research and teaching the history of art mainly around the question of the use of the work of art and its purpose. Beyond his teaching and writing efforts, he works in the field of contemporary art as part of a structure he created in 2004, Object de production. An economist-engineer from the École centrale de Paris, a graduate of the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, and holding a University of Paris-I master’s degree in the history of art, Poggi is currently preparing his doctoral thesis in art history under the supervision of Dominique Poulot on the topic of “the commerce of modern art in Paris under the Second Empire.”