Using documentary photography that prioritized home over street, Isabelle Bonnet invites us to enter British interiors of the 1970s. These photographs offer us signs of a new lifestyle henceforth centered on domestic space. There, the status of things speaks volumes, as does their number, their profusion within the working-class world, which contrasts with the spareness of bourgeois interiors. As for “taste,” the photographers hand it back to the inhabitants of these interiors without thinking that there exists a “good” or a “bad” taste.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Hartung-Bergman Foundation Seminar, September 2016

“Portraits” of Domestic Interiors in 1970s British Photography

Until the 1960s, the street—an emblematic figure of social space and of the working class—predominated in photography and in the British imaginary. In the course of the 1970s, with the emergence of a new generation of documentary photographers, there was a gradual shift away from the street and toward the hearth as well as an increasingly marked interest in domestic spaces. This turning point is reflective of a new lifestyle, now centered around the home, that had been fostered by rising prosperity, the appearance of novel models of consumerism, and the spectacular boom in television viewing.

Four series of photographs executed in Great Britain between 1970 and 1980 were devoted to portraits of anonymous people within their homes: June Street [ref]Series executed in 1973 during their final year of study at Manchester Polytechnic.[/ref]by Martin Parr and Daniel Meadows, Byker [ref]Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Byker (London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1983).[/ref]by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Middle England[ref]John Myers, Middle England (Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 2012).[/ref]by John Myers, and Belgravia [ref]Karen Knorr, Belgravia (London: Stanley/Barker, 2015).[/ref]by Karen Knorr. All of them offer a social and cultural overview of the United Kingdom during that decade: June Street and Byker look at working-class culture, Middle England at the vast middle class, and Belgravia the upper middle class. The shared aesthetic of these photos draws upon the resources of the “documentary style”:[ref]Olivier Lugon, Le Style documentaire d’August Sander à Walker Evans, 1920-1945 (2001; Paris: Macula, 2011).[/ref]their clarity and sharpness express their intention to provide meticulous descriptions as well as a deliberate absence of hierarchy among persons and objects.

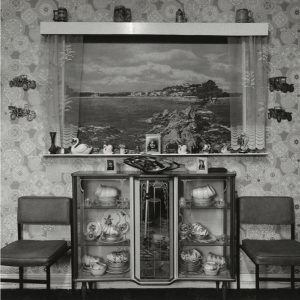

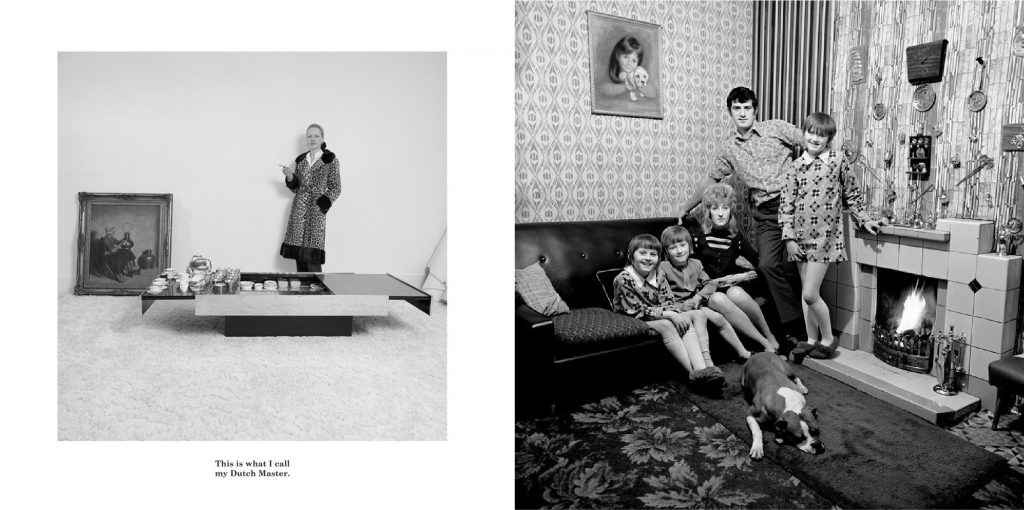

Fig. 1. On the left, Belgravia, by Karen Knorr © Karen Knorr 2017; on the right, Byker, by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen © Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen 2017

Material Space and the Place of the Body

Through its material culture, domestic space is a polysemic world. It is a point of convergence for our social and cultural identity. It reveals family interactions, structure, and values. It expresses our appropriation of the external world. It embodies our resistance or our submission to the norm. The space involved, the objects chosen, their accumulation or sobriety, the selection of standardized or brand furniture—all these things of daily life are signs of a taste that has been forged by what Pierre Bourdieu calls the habitus,[ref]Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).[/ref]that is to say, a social worldview produced by education and a class Unconscious that gives to each the “‘sense of one’s place.’”[ref]Erving Goffman, “Symbols of Class Status,” The British Journal of Sociology, 2:4 (1951): 294-304, see p. 297.[/ref]

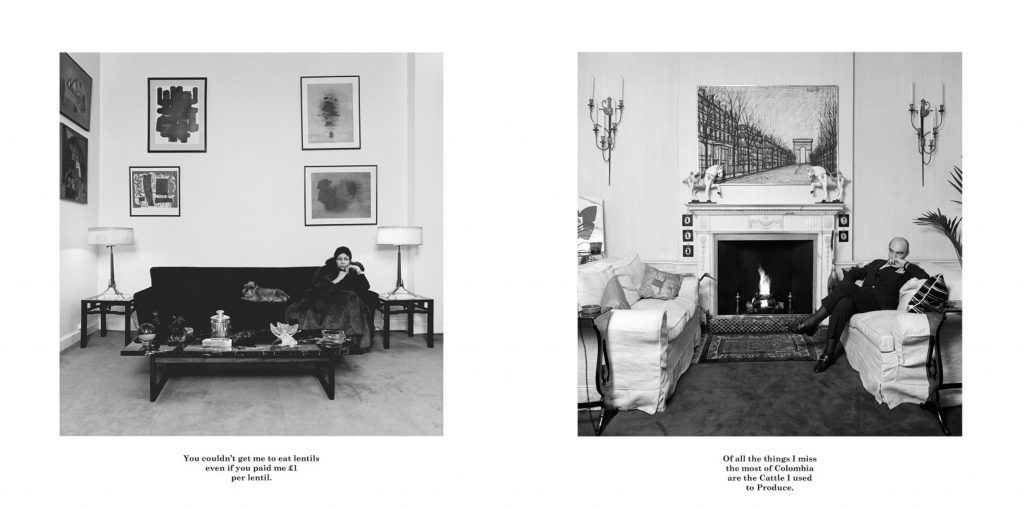

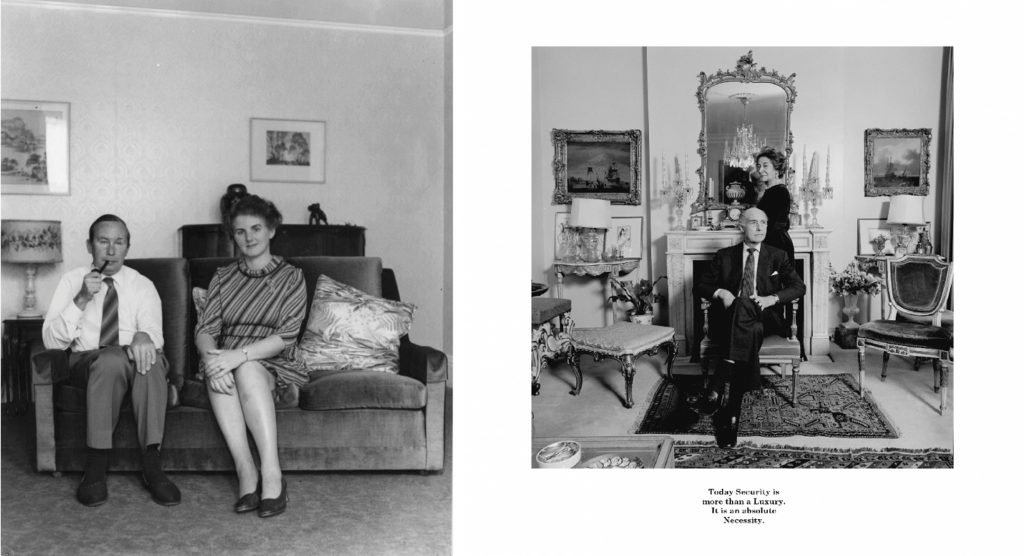

The greatest disparity is undoubtedly to be found between the spaces represented in the photographs of Belgravia and those of June Street and Byker. The working-class housing units are dark and cramped, unlike the airy and well-lit atmospheres found in the homes of the most privileged (fig. 1). Yet the framework of living in these differing spaces is not limited to the economic inequality involved; it occasions a peculiar relation of the individual to his body and to others’ bodies. Spacious or narrow, the environment thus determines one’s perception of its value in social space. The poses of the working-class or lower-middle-class models seen in these photographs are, when compared to those in the Belgravia series, edifying from this standpoint (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. On the left, Middle England, by John Myers © John Myers 2017; on the right, Belgravia, by Karen Knorr © Karen Knorr 2017

Wall Coverings and Furniture

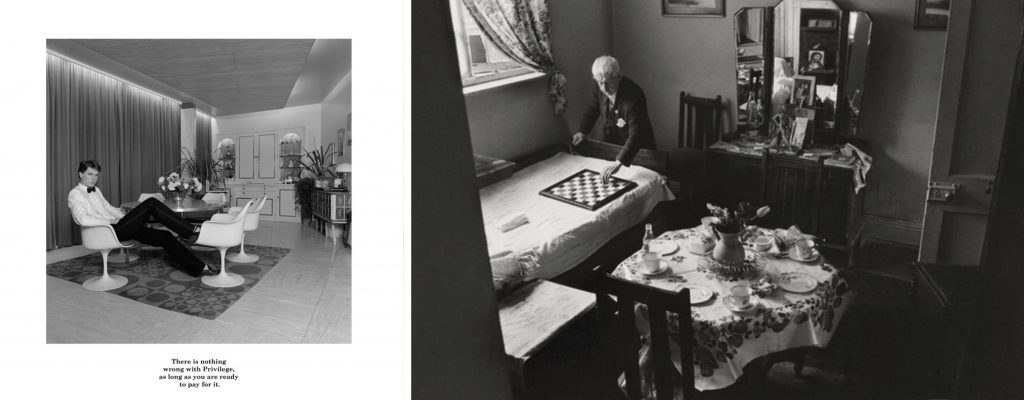

Parallel to this inequality of spaces are the decorative choices of the domestic environment, which express the most these social differentiations. The excess of patterned motifs in working-class interiors is answered by the asceticism of plainness and unobtrusiveness in those of the middle and upper classes (fig. 3). For the former, ornamental abundance exorcizes the specter of destitution and precariousness. It also wards off the gloom and filth of a sordid outside world. In the upper middle classes, on the other hand, an “economy of means”[ref]Bourdieu, Distinction, p. 177.[/ref] is a manifestation, precisely, of its means and becomes a model of social success for the middle class, which is often torn between the fear of seeming vulgar and the desire to act distinguished. While the latter might reject the almost Baroque luxuriance of the walls and carpets found in homes of a working-class culture, it shares with it, nonetheless, a taste for mass-produced furniture of indistinct style, often heavy and somber.

Fig. 3. On the left, Belgravia, by Karen Knorr © Karen Knorr 2017 ; on the right, June Street, by Martin Parr and Daniel Meadows © Martin Parr/Daniel Meadows 2017

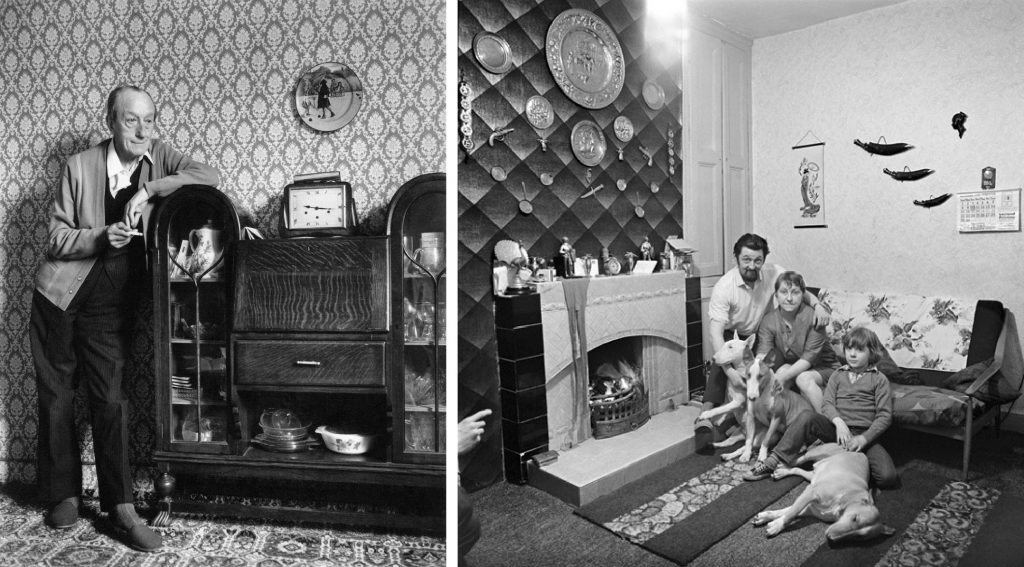

In a few of the June Street and Byker or Middle England photographs, one notes the display furniture, whose function truly is to show off and preserve one’s most precious possessions (fig. 4). While this furniture expresses very well one’s self-representation, it does not, for all that, make a show of expenditure, the “conspicuous consumption” described by Thorstein Veblen.[ref]Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of Leisure Class (1899; New York, Modern Library, 1934).[/ref]

The presence of genuinely antique or resolutely contemporary furniture is limited to the opulent Belgravia interiors. The possession of old furniture symbolizes dynastic continuity or, on the contrary, material success in search of legitimacy. Antiques are a sign of material as well as cultural inheritance because they manifest one’s familiarity with tasteful things. Through their contrast with mass-produced goods, they remove “the stigmata of industrial production.”[ref]Jean Baudrillard, “Sign-Function and Class Logic” (1969), in For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, trans. and intro. Charles Levin (n.p.: Telos Press, 1981), p. 43.[/ref] By employing a glossy neoclassical aesthetic, Karen Knorr gives to her images of the ruling “a sense of scientific classification.”[ref]Quentin Bajac, “Karen Knorr and British Photography of the 1980’s,” in Quentin Bajac, Kathy Kubicki, Alfonso de la Torre, eds, Karen Knorr (Cordoba: La Fábrica/Universidad de Córdoba, 2012), p. 19.[/ref] While it is not the function of contemporary objects to signify time, in the same way they provide distinction to their owner by championing a style that is opposed to the “absence of style” characteristic of mass-produced items.

Lighting as Social Marker

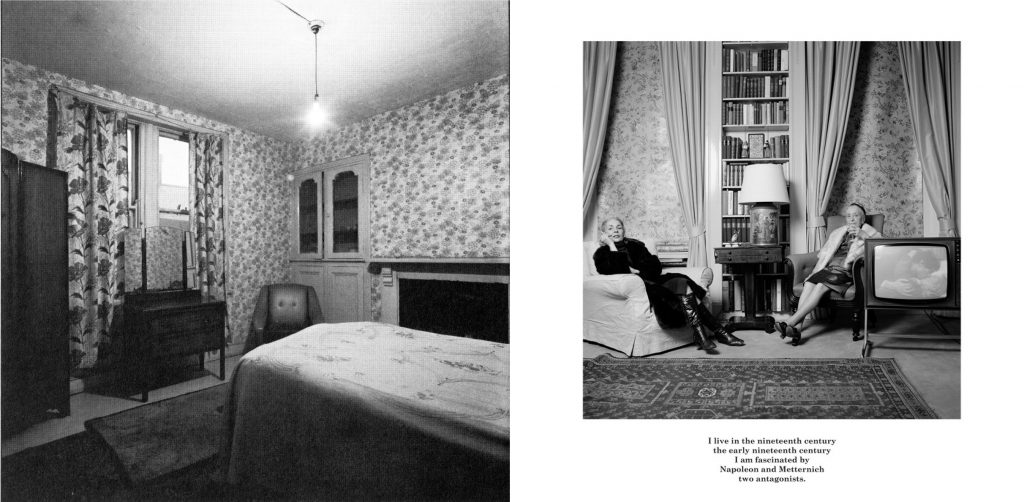

Often a little noticed object, the lamp is nevertheless a key social marker. Its proliferation or its scarcity signifies a recognition or a neglect of individual needs within the family setting. There is a correlation between the number of lamps and the notion of individuality, between the quantity of the lighting and education or culture. Richard Hoggart, who dealt with family life in working-class households, wrote: “to be alone, to think alone, to read quietly is difficult.”[ref]Richard Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working Class Life (London: Chatto and Windus, 1957), p. 36.[/ref] A second lighting source is added to that of the ceiling lamp in only three living rooms in the June Street series and only one interior chamber from the Byker series. In the Middle England and Belgravia photographs, on the other hand, a single room often has several lamps (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. On the left, Byker, by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen © Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen 2017; on the right, Belgravia, by Karen Knorr © Karen Knorr 2017

Image-Laden Decors

Abstraction does not exist within working-class culture, where naturalistic representation predominates. With the exception of a small reproduction of Jean-François Millet’s The Angelus in the home of an elderly lady—perhaps a reminder of the distant rural origins of the working class?—and of a tiny, strangely reframed Mona Lisa in the living room of a young couple in the June Street series, one finds in these domestic interiors neither copies of the “legitimate art” of the Fine Arts nor painted canvases. There are some simple posters or chromolithographs, always properly framed. A few artists seem to enjoy a broad success: the works of Lou Shabner, for example, whose chaste pinups inundated the British mass market, are present in several shots. With a constant display of gentleness in all its forms, these decorative images never represent working-class labor. On the other hand, nature is omnipresent in all its forms, with numerous landscapes, printed or in relief on plates, zoomorphic objects, and greenery in pots or as a pattern. This permanent hymn to nature in domestic interiors is indicative of the fact that it is absent from the outer environment (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. On the left, June Street, by Martin Parr and Daniel Meadows © Martin Parr/Daniel Meadows 2017; on the right, Byker, by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen © Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen 2017

By way of contrast, the walls of the Belgravia rooms are crammed with often old pictures, lithographs, and engravings. They fit into the same dynastic mythology as the objects and furniture. Nevertheless, while these works demonstrate a certain amount of cultural capital, they attest, too, to the conservative taste of these members of the bourgeoisie: even when contemporary, they belong to the avant-gardes of yesteryear and are already long recognized and well established. This absence of audacity, which prevails also in the choice of furniture, suggests that most of the residents from the Belgravia series belong to the business bourgeoisie, which is endowed with robust economic capital without, for all that, possessing great cultural competencies.

The Plentiful “Good Life”

One decorative object never to be found in the shots of the bourgeois interiors of Belgravia is the wall-mounted plate. On the other hand, it comes in all sizes, in earthenware, in copper, painted, or in relief in a majority of the working-class interiors from June Street and Byker as well as in a few of those from Middle England. Placed preferably above the mantelpiece, in the friendly confines of the living room, sometimes alone to mark the middle of the wall, sometimes in numbers in order to give rhythmic form to strictly symmetrical decorations, the plate is there to remind one of the importance of good cheer among the working classes. It celebrates the vital nourishment that gives strength to the body and compensates for days of hardship (fig. 8).

Fig. 8. On the left, Middle England, by John Myers © John Myers 2017; on the right, June Street, by Martin Parr and Daniel Meadows © Martin Parr/Daniel Meadows 2017

The Exhibition of Photographs

“Domestic emblems”[ref]Pierre Bourdieu, Luc Boltanksi, Robert Castel, Jean-Claude Chamboredon, and Dominique Schnapper (1965), Photography: A Middle-Brow Art (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990), p. 28.[/ref] par excellence, family photographs are barely present in the apartments from the Belgravia and Middle England series. They are displayed in large numbers over fireplaces or on sideboards of working-class interiors in Byker and June Street. Unlike ancestral portrait galleries, it is progeny that appear here rather than forebearers. Such autobiographical representation, long absent from working-class homes, explains their systematic exhibition and their absence in social settings more used to self-representation (fig. 9).

When the “Microcosm” Reflects the “Macrocosm”

Fig. 9. Byker, by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen © Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen 2017

These portraits of anonymous persons are so many portraits of domestic interiors that reveal the extent to which the material culture of one’s private space proves to be conditioned. They reflect a social identity rather than a form of individual expression. The June Street and Byker series testify to the peculiar culture of the working class but also to its resistance to the values of bourgeois good taste. To borrow the words of Joëlle Deniot, “It really is a matter, first of all, of an act of taste and not of bad taste.”[ref]Joëlle Deniot, Ethnologie du décor en milieu ouvrier, le bel ordinaire (Paris L’Harmattan, 1995).[/ref] Knorr’s highly constructed images refute as well as underscore in an ironic way the upper middle class’s “ideology of natural taste” that legitimates its rule. While the contrast is clear cut between these two extremes in the hierarchy, it becomes more nuanced in the middle class of Middle England, whose aesthetic—and place—oscillates between that of the upper middle class and that of the working class.

Brought together, what these photographs offer is a picture of pre-Thatcherite Great Britain: a sharply hierarchized class society in which the working class exists and still enjoys a respectable status. Yet this is also a society that has not yet integrated multiculturalism: the absence, in these photographs, of persons from the ex-colonies speaks for itself.

Bibliography

MEADOWS, Daniel. June Street. In Living Like This: Around Britain in the Seventies. London: Arrow Books, 1975.

KNORR, Karen. Belgravia. London: Stanley/Barker, 2015.

KONTTINEN, Sirkka-Liisa. Byker. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1983.

MYERS, John. Middle England. Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 2012.

BAUDRILLARD, Jean. “Sign-Function and Class Logic.” 1969. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. Trans. and intro. Charles Levin. N.p.: Telos Press, 1981.

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Trans. Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

_____. With Luc BOLTANSKI, Robert CASTEL, Jean-Claude CHAMBOREDON, and Dominique SCHNAPPER. 1965. Photography: A Middle-Brow Art. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990.

DENIOT, Joëlle. Ethnologie du décor en milieu ouvrier, le bel ordinaire. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1995.

HOGGART, Richard. The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working Class Life. London: Chatto and Windus, 1957.

MILLER, Daniel. Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors. Oxford: Berg, 2001.

SEGALEN, Martine, and Béatrix LE WITA. Eds. Chez soi, objets et décors: des créations familiales? Paris: Autrement, 1993.

STASZAK, Jean-François. “L’espace domestique: pour une géographie de l’intérieur.” Annales de Géographie, 620 (2001): 339-63.

After having worked for twenty-five years in fashion photography, Isabelle Bonnetresumed her studies in Art History in 2011. Her Master’s thesis, written under the supervision of Michel Poivert at the University of Paris-1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, brought together British photographs from the 1970s around the theme of the portraiture of domestic spaces. She has just published an article on the photographing of transvestites in Sébastien Lifshitz’s book, Mauvais genre, Les travestis à travers un siècle de photographie amateur (Éditions Textuel, 2016).