In The Ephemeral Museum, Francis Haskell decried the new hegemony created by major art exhibitions and the harmful consequences thereof. He recalled the genesis of the ways in which art works circulate as well as, from the early twentieth century, the first loans of paintings for prestigious international exhibitions, the establishment of ties between museums and other institutions, and the role played by various forms of nationalism.

Exhibitions have always been sites of legitimation and regulation for artistic life and for the market. The history dates back to the seventeenth century and to the first salons organized by the young Academy of Painters and Sculptors, which tried to curb a movement toward self-management on the part of artists. Thus, toward the middle of the seventeenth century, a certain Martin de Charmois could complain to the royal family about artists who wanted to shake off their status as artisans by keeping shop themselves and securing their own market.

We know what followed, with salons organized by a powerful Academy ultimately coupled with juries that were more open to varied selection criteria. From a still rather simple system affecting a still rather limited and homogeneous world, we have passed over to an ever more complex situation with an ever greater number of actors, sites, and objects for the use of vaster and vaster populations. One need only examine to what extent Biennials have proliferated since the 1990s, establishing themselves now as genuine artistic phenomena in their own right as well as for purposes of tourism and diplomacy and with regard to economic and political considerations.

Paul Ardenne and Olivier Berggruen, who are art historians as well as exhibition curators, have had many years of experience dealing the events that punctuate international artistic life. The assessments they have drawn up are both informed and critical: acceleration, globalization, and standardization of the norms of legitimation as well as of the sites of presentation; cross-fertilization among institutions that have become interchangeable; the preeminent place of art fairs, of show business [du spectacle], and of economics, with elitism and populism combined amid unequal exchanges between the West and its partners.

In this respect, islets of resistance–if not breaches–do indeed exist. But to some, the political condition of art will seem to be determined largely by positions that might aim more at maintaining a bogus exoticism than at inventing a true dialogue with new arrivals on the market. Others will see the extension of the domain of art as a privileged site for tensions wherein questions of identity and power are tirelessly raised over and over again through breaking down existing fiefdoms and by an effort to activate the world’s thought.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of June 29, 2006

Olivier BerggruenThe Time

of Changes

Developments that can be observed on the arts scene over the past few decades leave little room for doubt: marked by the effects of globalization, the situation of art today reflects the trace of commercial exchanges between the West and its partners (and sometimes its ideological adversaries, like Cuba). The same institutional structures are to be found in all four corners of the globe as the art market extends its reach almost everywhere in the world. It is also well known that contemporary art is the mainstay of this market; museum policies are centered in large part around the dissemination of this kind of art, and the exhibition and production networks that are established among museums, artists, galleries, critics, collectors, and the specialized press are heading in the direction of standardization, just like Western-led economic globalization. Another phenomenon in this process of cultural regularization involves the holding of major exhibitions such as biennials and other large-scale events, which are being organized at a brisk pace, whereas in the public mind art fairs have replaced biennials (I shall return to this point).

The Triumphs of the Market

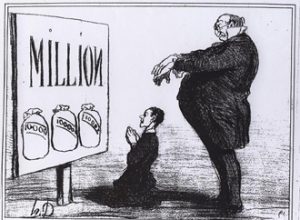

Let us pause for a moment to take a broad overview of the universe of contemporary art. Artists, galleries, dealers (those involved in the “secondary market,” to use the American expression, that is to say, resellers of works that have already been put on the market), art critics, museums, private foundations, art historians, public partners, sponsors, advertisers, and auction houses play the roles industrial and commercial Europe had assigned to them in the nineteenth century. This expansion of the art world reached its zenith with the building of the major European and American museums, the creation of New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1929 symbolically marking the date when contemporary art became the object of all desires. And yet, while in the past these just enumerated groups fulfilled well-defined roles, what the present-day world encourages is their cross-fertilization. To take one example, major commercial galleries are now opening spaces that look just like museum rooms; they organize retrospectives that many museums would be prepared to receive (partnerships between the public and private sectors have indeed become quite common) and they publish luxuriously printed catalogues. What we are witnessing, therefore, is an overturning of hierarchies when some New York gallery owner has more influence than most museum directors. Conversely, some administrators have been lured by the commercial world and are now working for galleries or auction houses. More disturbing is the fact that, in light of the unprecedented craze for contemporary art, some museums are surrendering their independence to the benefit of products brought out by the market, sometimes doing so under pressure from the kind of trustees one finds in the English-speaking world; they thus give up their independence and yield to the pressure of the kind of conformism that is dictated by the art market.

In this planetwide art world, a dominant view, the market’s, seems to be triumphant. As the contemporary arts scene has developed, the structures for receiving art have multiplied. And faced with the diversity of these initiatives, biennials are assigned the role of clearing the ground and of setting in order the often chaotic forces in play. But in fact, the art market itself regularizes the situation much more forcefully than any effort on the part of critics or institutions. Now, the world of major exhibitions is currently experiencing discomfort due to its fear of being supplanted by trade fairs.[ref]This fear was expressed during a colloquium on the future of the Biennale organized in December 2005 by Robert Storr in Venise (“Where Art Worlds Meet: Multiple Modernities and the Global Salon,” Palazzo Cavalli Franchetti).[/ref] And yet, do not biennials, too, fit into the logic of the market? Whatever the case may be, the first and foremost of them, the one that serves as the prime example–Venice–was created a century ago in order to claim a cultural and commercial position that had already been inaugurated, a bit, during the pre-Napoleonic era. Relations between the Biennale and the commercial world were, so to speak, natural: commissions on the sale of art works served to finance the Biennale until the student movements of 1968 put an end to this system.

Between Elitism and Populism

We thus arrive at a situation in which major international events, fairs, and museums share complementary roles. The cultural landscape takes on easily recognizable forms in which major brands dominate. To cite one example, the general policy of the Guggenheim–the first arts multinational–encourages such standardization when exhibitions circulate from one “branch” to another, between Berlin, Venice, Bilbao, and New York (as was the case with a retrospective of the paintings of Jeff Koons)[ref]It will also be noted that museum collections often serve as instruments of exchange between major institutions and new public or private partners who wish to participate in the culture market. Of course, the circulation of art works is not reprehensible in itself, on the contrary; but, as Philippe de Montebello has underscored in a recent speech, the unfortunate consequence of such a policy is sometimes that it excludes from the dialogue institutions that often are deserving but lack any real power of their own.[/ref]. Each year, the Guggenheim gives a prize to the best artist chosen by an international jury, just as the Biennale awards a prize to one of its participants. In their own way, auction houses also create winners and losers. They do this so well that, in the view of the public, these institutions take on easily interchangeable identities. Moreover, the standardization of cultural networks goes beyond “contents” and extends to the “containers”: from one continent to another, the ways in which works are presented all head in the same direction: toward white, smooth, and anonymous spaces (the “white cube,” which has lent its name to one of the main London galleries), sober good taste, and a technocratic-looking concern with efficiency–in short, a postindustrial aesthetic only a few architects succeed in pulling off. A similar conformism reigns over the tools of art’s dissemination, such as the specialized reviews that often have recourse to the same jargon as critics use, for there exists a language specific to contemporary art that would be worth studying as a striking symptom of the way the art of today operates.

Let us now come to the question of the dissemination of contemporary art in an overall context. If art is experienced as a product of exchange, it is, in my opinion, caught between two contradictory forces: on the one hand, its dissemination and propagation according to the methods of advertising and commerce; on the other, an aura of exclusiveness that keeps it in a situation of autarchy. There are, therefore, two forms of discourse that come across, one elitist, the other populist. One of these forms of discourse is populist, for the democratization of cultural institutions coincides with an increase in the number of sites where art is received; art claims a greater affinity with other modes of communication, which are often popular ones, such as movies, television, fashion, advertising, and so forth. In the main, contemporary art rests less on knowledge inherited from nineteenth-century sorts of institutions (opera, theater, mythological texts, knowledge of literature and poetry) than on conventions that are expressions of popular culture. The other discourse is elitist, because art has been erected into a mode of thought, sometimes an esoteric one, and constitutes a form of discourse about itself, as in the work of Ryman and Richter. Without having some references to its history, without knowledge of the games in which it indulges with increasing gusto, understanding contemporary art is a difficult undertaking. A turning point seems to have occurred since art was turned into a mode of thought (thanks to Marcel Duchamp), yet this is a kind of thinking that remains essentially visual.

Beyond the issue of learning certain rules, there is, however, also the question of people’s access to culture. While networks for teaching and disseminating art have developed, it remains no less the case that the entrance fee has become more expensive than ever and is reserved for an elite that formerly was intellectual and artistic and that today is financial and media driven. Such access requires considerable capital–on the part of galleries whose operating costs are dear and on the part of collectors who are sometimes caught up in the game of their speculative ambitions, while critics have themselves become fully involved in the extant commercial stakes (prefacing a gallery’s exhibition catalogue is the most lucrative activity an art critic can undertake). The people who make up these networks live in a parallel universe, an obligatory circuit made up of trips from one major exhibition to the next and encounters in a privileged world on the occasion of openings that are followed by sumptuous dinners. There is no question of decrying this state of affairs but, rather, of showing that, though this accelerated globalization, the West is extending its domination.

The Dominant West and its Islets of Resistance

The question of cultural dialogue between the West and its partners raises a certain number of problems, beginning with that of the equality of relations. No one challenges the dissemination–or the teaching–of contemporary art on a planetary scale. South America and Japan for generations, Africa more recently, and China and India, too, participate in this process of “exchange.” Nevertheless, it can be asked whether such democratization does not constitute a new sort of colonial project, since the West is exporting its cultural institutions into countries whose traditions are relatively different. (One need only mention the case of countries in which the production of art is connected with religious considerations.) The arts of these countries nonetheless find their place within an overall, worldwide context; their artistic productions, even traditional ones, exist in contact with other artistic forms on which they nourish themselves. (This is not the place to go any deeper into this complex question, but any attempt to exclude non-Western arts from aesthetic discourse ends in a form of exoticism that constitutes a glaring mistake.) A certain vision of art has been imposed somewhat all over the world, without for all that stifling local or regional initiatives–often fecund forces of resistance are built up through contact with the West. As proof of the complexity of the relations between former colonizers and the colonized, take the example of the kind of art that developed in Brazil during the 1960s under the impetus of Neoconcretism (sometimes given the name Tropicalismo). For Hélio Oiticica and, more recently, Cildo Meireles, the notion of representation and transposition of a cultural identity is replaced by one that consists in appropriating for oneself what the West produces, absorbing it and digesting it in an anthropophagic way. This typically Brazilian mode of artistic operation derives in large part from the writings of the poet Oswald de Andrade.[ref]Oswald de Andrade, Manifesto Antropófago, 1928.[/ref] Or, to cite another example, there is Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work, whose power has been its ability to integrate into the dominant pictorial discourse heterogenous features coming from “underground” cultures. The forms of artistic discourse are renewed with the launching of this cultural brew. There is, therefore, always a possibility of subversion of conventional modes, right inside postindustrial society.

That said, distribution of information is still handled by the West, and the dominant cultural operators are Western. The situation of major exhibitions such as biennials is to be instruments that guarantee the maintenance of this status quo. Yet within the system, breaches open–often remarkable attempts to call back into question the present-day situation (the Havana Biennial and, often, the work of South American and African curators). Though these breaches, we discover that the dominant discourse, far from being inflexible, is liable to be turned against itself–via initiatives that consist, precisely, in displacing these institutions geographically and culturally. Hélio Oiticica wore carnival costumes (called Parangolés) that asserted the fluidity of his artistic stance, somewhere between the aesthetic realm and lived experience; the American artist David Hammons had exhibited a few objects on a New York street corner; the Indian dancer Sharmila Desai is rethinking the role of the traditional artistic disciplines in her country of origin by transposing them within the context of the contemporary arts scene. Such initiatives assert a vitality that draws its source at the margins of the dominant system–proof positive that this system offers the possibility of dialogue with other ways of apprehending art.

A Biennial as a Place of Reflection

My conclusion is, at the very best, provisional. Within the context of an international arts scene, geographic or ethnic origins no longer have the determining character they once had (even though, as we have just seen, some artists claim a geographical specificity–and yet, such a specificity is articulated in the light of a confrontation with the West). Aesthetic regularization is assured, for better or worse, by market forces whose mark is not imposed in some uniform way. While it is true that the traditional institutions of Venice, Bâle, Miami, and Kassel are reinforced, contemporary art has the capacity to escape from hegemonic forces by espousing the forms of a discourse that is capable of questioning the very structures of its creation and dissemination. Robert Storr, curator of the next Venice Biennale, has made himself the spokesperson for alternative modes of presentation, conjuring up the spirit of the Salons at the time of Diderot and the Enlightenment. For my part, I would like to imagine the future of biennials not as weakened under the weight of efforts at standardization but as places of reflection. Why not underscore the role of biennials by opposition to institutions that graft themselves onto their successes? And why not affirm their specificity? Short of renouncing their ambitions to become museums and encyclopedias, it is incumbent upon biennials to create spaces of dialogue, confrontation, and diversity for contemporary art.

Bibliography

Alloway, Lawrence. The Venice Biennale, 1895-1968: From Salon to Goldfish Bowl. London: Faber, 1969.

Jones, Caroline A. “Troubled Waters–Globalism and the Venice Biennale” Artforum, February 2006: 91-92.

Montebello, Philippe de. “The Art Museum and the Public Trust.” Lecture given at the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2002. Privately printed, May 2002.

Newhouse, Victoria. Art and the Power of Placement. New York: Monacelli Press, 2005.

Olivier Berggruen , who was born in Switzerland, studied art history at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island and at the Courtauld Institute in London. He worked briefly in the Impressionist and Modern department of Sotheby’s London office before opening a modern and contemporary art gallery in the early 1990s. Since 2002, he has been associate curator at the Shirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. Berggruen has also curated several major international exhibitions, notably “Henri Matisse: Papiers découpés” (Frankfurt and Berlin, 2002-2003) and “Yves Klein” (Frankfurt and Bilbao, 2004-2005). For 2006, he is preparing a retrospective on Paul Klee’s work (Santander and Rome) as well as an exhibition around the theme of “Picasso and the Theater” in Frankfurt.