In the middle of the nineteenth century, the reaction against spiritualism was a prelude to the struggle that would start up against art for art’s sake–against art seen as autonomous and rid of all social responsibility. A certain number of thinkers paved the way at the time by attacking this vision of an ethereal, deceptive, and stupidly comforting world, and they showed that the Heaven of Platon or Bossuet was but a sorry refuge when what was needed was to face reality. In his Philosophes classiques du XIXe siècle (Classical philosophers of the nineteenth century, 1857), Hippolyte Taine called upon people to take up again the realist tradition and to place themselves on the ground of facts and science.

It is well known to what extent this return to the real was ill greeted by the critics, who denounced its hideous materialism and its obsession with evil. With no Hereafter, this sort of realism could be the harshest kind possible and the most resolutely opposed to any kind of moralizing aesthetic. Behind its expressions of detestation loomed a critique of Germany that, starting in 1870, was to combat, inch by inch, the spell of a nation Madame de Staël had cast in De l’Allemagne (Germany, 1814). The liberal union of neighbors (a prefiguration of Europe) so wished for by the Renans and Taines was then jettisoned in favor of a return to a France injured in its pride and ready for revenge.

While one side of the French intellect shut itself off amid its feelings of disenchantment, the other side devoted all its forces to a reconstructive effort. It was in the wake of this energetic rebirth that the idea prospered of creating a kind of art that would be so connected with social life and morality that it could change the old world. Indeed, between 1889 and 1914 debates were rife around the topic of “social art.” As Catherine Méneux shows, social art could not completely deny the autonomy and freedom of action gained from modern artists. In an industrial society that was undergoing a complete reshaping of its economic, political, and religious framework, art was one of the symbolic objects numerous actors took up in order to invent a more just society–one in which each person would have access to culture, to beauty, and to harmony in the private realm as well as in the public space. We rediscover, in this way, the premises of Saint-Simonism, the philosophy of Taine, and the rationalism of Viollet-le-Duc, to which were added anarchist impulses and, from abroad, the efficacy of the English (with William Morris, especially) and Belgian models.

Christophe Prochasson insists upon the exceptional character of this turn-of-the-century history, a “moment” in which it seemed possible to bring art, politics, and science into harmony. He is very well aware of the contradictions that were inherent in these hopes of seeing art reconciled with the people when the latter were viewed as alarming on account of their mass character and their supposed absence of “good” taste. Added thereto were social art’s numerical weakness and the paucity of its real achievements, followed by the funeral toll of the Great War.

Defense of a kind of art that would be both modern and French was, of course, blocked by the outbreak of world conflict. Yet it was to reemerge in the 1920s and 1930s in new ways and with a clearer, State-led willingness to act whose effects could be felt above all at the 1937 International Exhibition of Arts and Technologies. After the combats in favor of “social art” came the intestine struggles of anarchists who had defended modernity against the eternal poverty advocated by their theorist Peter Kropotkin, and there were fights with Picasso, too, who had so established himself as the artist capable of linking together modern individual freedom and history that Robert Delaunay could cheekily declare in 1935: “Me, artist, me manual worker, I’m making revolution right on the premises.”

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of September 21, 2006

Christophe ProchassonNeither Doctrine

nor School

nor Movement

It is not easy to broach the question of “social art.” More than is the case when confronted with other notions commonly employed in art history or cultural history, one stumbles here over the definition. Is one dealing with a “school,” a “movement,” a “sensibility,” or else, as Catherine Méneux discreetly suggests, a “moment” in the sense this term is meant sometimes in the history of ideas? This last path is undoubtedly the most appropriate one for understanding what this attempt to harmonize turn-of-the-century art, politics, and science was about.

While “social art” was discussed among groups and in reviews, while it was the topic of various investigations, colloquia, and congresses, and while some strong personalities–like the critic Roger Marx–became its fervent converts, it would be quite hard to give it the contours of a well-established aesthetic doctrine. “Social art” was neither a doctrine nor a school nor even a movement. It was more a question artists posed in their time–that four-decade-long period separating the inception of the Third Republic from the outbreak of the Great War–and which the men of that time, politicians, critics, and intellectuals, admen and union or political activists, posed, in turn, to artists.

One can easily understand that, among the “numerous problematics” to which a historical examination of social art is related, those concerning modernity and utility are at the top of the list. Méneux mentions the 1934 manifesto of the Union of the Modern Arts, certainly beyond the end of this brief history, which is authentically expressed: “modern art,” it can be read there, “is a genuinely social art.” Contemporary art is to be useful in the life of those who contemplate it or, better put, who find themselves immersed in it. Early traces of such conceptions undoubtedly can be found at the beginning of the nineteenth century, in particular in the writings of those conventionally called the first socialists. But an entirely other context frames those initial proposals in favor of social art: after the French Revolution, a world had then to be rebuilt. At the other end of the same century, social art answered to a wholly different set of worries as well as to wholly other hopes.

From Méneux’s talk, I shall retain two features that offer us a fresh interpretation of social art. First of all, she brings out the connection between proposals drawn up around the theme of “social art” and those emanating from what Christian Topalov has called the “cluster of reform”: they shared the same concern with modernizing society by reforming it according to the laws brought to light by science and within the framework of a process of democratization initiated by the new republican regime. Indeed, these two networks overlapped: the same men circulated among the various reviews, congresses, and cultural institutions, such as the People’s Universities of the 1890s, which dealt with social art and the social sciences, with both to be placed in the service of calm and rational social reform, thereby uniting the beautiful and the useful.

Oscar Roty, one-franc coin with “The Sower »

This is why social art did not present itself as a new aesthetic doctrine or even as a coherent movement in search of some essentialized view of the Beautiful. It was a perpetual quest, buttressed by the social background of its time, to which it attempted to give a new packaging adapted to the needs of the majority. Thus, the authors who made themselves its defenders usually privileged the most public forms of art: architecture and theater, posters and the knickknacks of everyday life that were invading the domestic realm, like those “minuscule objects,” stamps, and coins that had become so commonplace that they seemed to have become invisible. Roger Marx, undoubtedly the greatest figure in social art, demonstrated a pronounced interest in them in his work published in 1913. Nothing is contemptible among the things that populate the everyday life of society’s humblest members. By regular immersion in the beautiful and through those objects or pieces of furniture that make up the horizons of men without quality, it was hoped that an uplifting of the soul and an education of taste would result with huge consequences for civilization. In the most socialistic of these gambles, what was hoped for was a simultaneously moral, aesthetic, and social revolution.

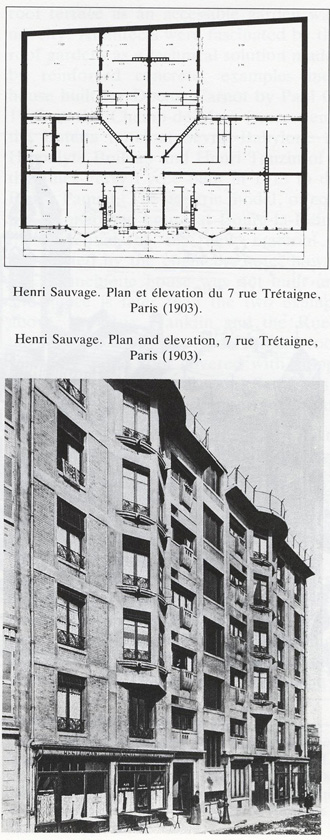

Henri Sauvage and Charles Sarazin, Building at 7 rue Trétaigne, Paris (18th arrondissement), 1903, for the Hygienic Society of Low-Cost Housing.

The second illumination offered by Méneux’s contribution sheds light on the reaction various versions of social art had against the disturbing invasion of mass culture. Indeed, this reaction could include “reactionary”–or, if one prefers, “traditional” and antimodernist–dimensions. Such dimensions therefore stood in contradiction to the modernizing tendencies noted above, which had led many theorists and creative artists to engage with modern industry or to seek the most contemporary forms and materials. This contradiction seriously complicates our analyses of social art. It is already present, indeed, as Méneux recalls, in the work of one of this movement’s major references, William Morris, a great admirer of the Middle Ages and theorist of useful beauty set against the pretensions of art for art’s sake.

Jean Lahor, mentioned by Méneux by way of an example, made no secret of his dread of “the rising tide of democracy” and of the “tasteless crowds.” There clearly is in social art a desire to protect against the ugliness of the demeaning modern world. Yet in the end, this critique was rarely conservative. It contrasted a democracy that, through laziness and neglect, abases one, turning over to industrialists and shopkeepers the aesthetics of the world, with a democracy that raises one up. The latter puts artists up front and invites them to hear the messages of contemporary civilization, where industry and technology have taken on such an important role. It is possible to be creative, as Francis Jourdain, son of the architect Frantz Jourdain, was in his “modern workshops,” making modern pieces of furniture that were not more or less overt replicas of the Louis XV style. As for the father, Frantz, he had battled against the architectural pastiches that were cluttering up the urban landscapes of his time and that seemed to betray an exhaustion of inspiration on the part of his contemporaries in the field of architecture.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Inter Artes et Naturam, 1890, 295 x 830 cm, Rouen Museum of Fine Arts

Such lovely proposals, full of aesthetic and social optimism, stood in sharp contrast to the nagging despair of fin-de-siècle decadentism. What kinds of productions did these proposals lead to? Méneux is not wrong to note “a crucial lack of implementation”–with, it is true, a few notable exceptions, as in the case of Francis Jourdain and even some collective firms like Louis Lumet’s or perhaps what was accomplished within the framework of the People’s Universities–though briefly so, in the last case, since the People’s Universities movement gradually collapsed starting in the year 1902-1903. Neither can one help but be struck by the concrete aesthetic choices made by the “theorists” of social art–that is, inasmuch as this term, as we have shown, would be suitable at all for designating such a heterogeneous “intellectual moment.” These Moderns thus rallied to then-extant forms that are not generally listed in the files of modernity, and still less in those of the avant-garde. This does not mean, of course, that such productions would not have appeared modern in their time. One may thus be surprised to see Puvis de Chavannes ranked among the major heralds of a new kind of art [d’un art nouveau] on account of the decorative character of his works and of the public places in which they were exhibited, often thanks to public commissions which thus gave them a social dimension. As a result, the conservative Puvis was praised to the skies by progressive artists and writers and even by Left or Far-Left politicians such as Jean Jaurès. Méneux offers an explanation for this paradox to which one can indeed subscribe: such choices were made, in a way, for want of anything better. Social art leaned on this new art for support because the latter seemed the least far removed from a few of the proposals it was making, although social art could also sometimes distance itself from it.

Jules Chéret, “Allegory” for the New Paris. Published in La Critique, February 1904.

Should one, for all that, speak of failure ? With this term, we employ a mode of evaluation that is perhaps neither the most historical nor the most relevant. That is so, first of all, because it is uncertain whether the more or less theoretical artisans of social art in all its forms themselves lived this intellectual and artistic adventure as a “failure.” Next, because the 1914 War was one of the major reasons for the collapse of these projections for the future (think, for example, of the project of an international exhibition of the modern decorative arts for the year 1916 contained in the 1912 Roblin report, which could not take place as a result of the war). In the end, a great deal was produced: numerous, rich reflections distilled in various intellectual reviews, but also original undertakings like the Civic Theater or the Theater of the People inaugurated by Maurice Pottecher in 1895. One could also mention the short-lived associations that were formed at the time: Art for All, the International Society for People’s Art and Hygiene created by Jean Cazalis, where there was a convergence between the aspirations specific to “social art” and those one finds expressed in the “cluster of reform.” The balance sheet is perhaps less “disappointing” than Méneux intimates, in so pessimistic a way, in her excellent presentation.

Bibliography

L’École de Nancy, 1889-1909. Art nouveau et industries d’art. Catalogue published on the occasion of the École de Nancy, 1889-1909 Exhibition organized by the city of Nancy. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999.

Loyer, François. Ed. L’Ecole de Nancy et les arts décoratifs en Europe. Metz: Éditions Serpenoise, 2000.

Mercier, Lucien. Les Universités populaires: 1899-1914. Education populaire et mouvement ouvrier au début du siècle. Paris: Les Éditions ouvrières, 1986.

Mil neuf cent. Revue d’histoire intellectuelle, 7 (1989). “Les congrès, lieux de l’échange intellectuel. 1850-1914.”

Mil neuf cent. Revue d’histoire intellectuelle, 21 (2003). “Art et société.”

Prochasson, Christophe. Les intellectuels et le socialisme, XIXème-XXème siècle. Paris: Plon, 1997.

Rebérioux, Madeleine. “De l’art industriel à l’art social: Jean Jaurès et Roger Marx.” La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, February 1988.

Topalov, Christian. Ed. Laboratoires du nouveau siècle. La nébuleuse réformatrice et ses réseaux en France, 1880-1914. Paris: Éditions de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 1999.

Christophe Prochasson is a Director of Studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. Specializing in the political and cultural history of contemporary France, he has published numerous works on the history of intellectuals, of socialism, and of fin-de-siècle culture. Prochasson is also a specialist of the history of World War I. Among his latest works are: Dictionnaire critique de la République (co-edited with Vincent Duclert, Flammarion, 2002), Vrai et Faux dans la Grande Guerre (co-edited with Anne Rasmussen, La Découverte, 2004), Paris 1900. Essai d’histoire culturelle (Calmann-Lévy, 1999), Saint-Simon ou l’anti-Marx (Perrin, 2005). He has just completed preparation of a historiographical essay: L’histoire à l’estomac. Politique, Emotion, Histoire.