Brett Littman a travaillé dans le courant alternatif à New York downtown et retrace l’historique des formes d’art et d’expositions non-institutionnelles, des années 1960 à aujourd’hui. Il nous aide à mesurer la force d’actions qui n’ont pu prospérer que sur fond de contestation générale du capitalisme et de la politique engagée au Vietnam en particulier. Ces expériences ont duré pour un certain nombre, mais dans un paysage radicalement modifié par de nouveaux paradigmes qui voient l’économie dominer toute forme de fait social.

Georges Armaos revient de son côté sur « la règle du jeu » du marché de l’art newyorkais dont la surchauffe ajoute à l’étrange aura. Il passe en revue le rôle de chacun des acteurs, sur une scène artistique de plus en plus dirigée par les marchands au détriment des musées et de la critique.

Dans ce paysage, il reste à écrire l’histoire internationale des moyens que se donnèrent les artistes de tous les temps pour échapper à leur condition de pions sur l’échiquier des sociétés consuméristes qui préfèrent régulièrement prendre l’art comme une denrée à la fois magique et rentable.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Séminaire du 17 janvier 2008

Changes in New York Galleries

from 1945 until the present

Georges Armaos

Ladies and gentlemen, I would like to begin by thanking Laurence Bertrand Dorléac for her invitation to this seminar and for her encouragement and support to think about the history of art galleries in New York. I would also like to thank Sebastien Délot, who is currently preparing a Ph.D. dissertation on the history of art galleries in New York and Paris, for his bibliographical references that allowed me to prepare this speech.

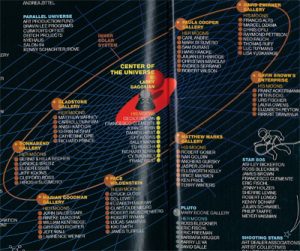

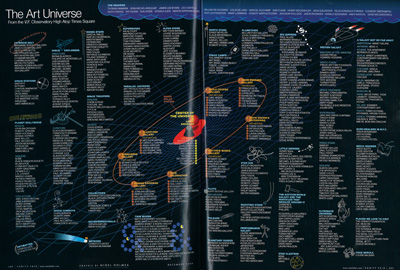

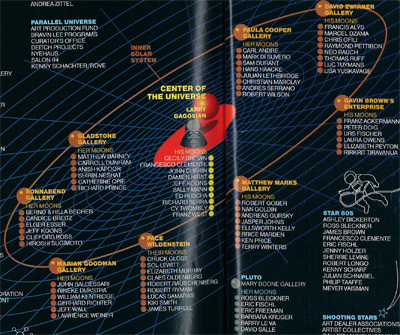

Vanity Fair. Double page, publihed in December 2006, no 556, pp. 340-341, Illustration Nigel Holmes.

As you already know from her introduction, I came out of the academic world, where I specialized in modern and contemporary art. I entered what is called the art market through relationships and by necessity. I have worked with three galleries in Paris, Los Angeles, and New York. These experiences, including friendships with some artists, dealers, and collectors, have allowed me to gain an idea of how these small- and medium-sized companies operate on a day-to-day basis. To say that I’m a specialist of the history of art galleries in New York would be far-fetched. I don’t think there is anyone who could claim to have followed everything that has happened in that extraordinary city–with the sole exception of Irving Sandler, who has, in his own peculiar way, narrated the changes that have taken place in the art scene there.

Before getting into the thick of it, I have to warn you that I am not going to talk to you about the entire world of contemporary-art galleries in their broadest accepted definition. For, that would include everything that is being created and presented by living artists. In New York, as in many other places, there is a multiplicity of parallel artistic universes. The universe that will interest us tonight, one way or another, is the one that plays a significant role in the construction of what we commonly call art history. There are hundreds if not thousands of galleries that present contemporary art but that have absolutely no role in what ends up in the collections of museums and, ultimately, in the constantly changing canon of art history.

Vanity Fair. Double page, publiée en Décembre 2006, no 556, pp. 340-341, Illustration Nigel Holmes. (detail)

If I have chosen to survey, or simply touch upon the surface of, the history of art galleries in New York, that is because, more than any other city in the world, New York has been and continues to be one, if not the most important, center for contemporary art. World War II played its part in the migration of European artists to this city. But there are many more reasons that can be summoned up for any attempt to explain the advent of contemporary art and to provide an account of the galleries that have exhibited and promoted it. To name but a few: the health of the post-World War II US economy; federal and state legislation that offers tax incentives to the donors of works of art or financing for such nonprofit organizations as museums; the habits, sense of duty, and influences of the upper classes and the wealthy; the relatively brief history of American art; its use as a propaganda tool during a substantial part of the Cold War; and the weight and influence of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, the Guggenheim, and many other smaller structures located there.

Laure de Coppet and Alan Jones, The Art Dealers. The Powers Behind the Scene Talk About the Business of Art, Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., Publishers, New York, 1984.

Allow me to show you the list of gallery owners and dealers interviewed by Laura de Coppet and Alan Jones at the beginning of the 1980s for a book published in 1984 under the title The Art Dealers: The Powers Behind the Scene Talk about the Business of Art. (Figure 1) What you have here is a “still shot” of some of the personalities who have shaped contemporary art. I recommend a critical reading of these interviews. In spite of its mythological character and of all that is left unsaid, this volume is worth a look if you want to understand how these people were thinking about their profession and what difficulties they encountered along the way. Everybody knows the role played by Peggy Guggenheim right after the War or that of Betty Parsons (Gottlieb, Newman, Reinhardt, Pollock, Clyfford Still, Kelly, etc.), Charles Eagan (de Kooning, Kline), and Sidney Janis (Kandinsky, Mondrian, Schwitters, and Albers, then the artists of Betty Parsons). To these names I would add: Pierre Matisse in the 1950s (Dubuffet, Matisse, etc.); Leo Castelli (Johns, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Stella, Rosenquist, Serra), Andre Emmerich (Frankenthaler, Olitski), and Ileana Sonnabend (Penck, Gilbert and George, Kounellis, Sugimoto) in the 1960s and 1970s; Marian Goodman and Paula Cooper in 1970s; Mary Boone, Jeffrey Deitch, and Pace then PaceWildenstein in the 1980s and 1990s; and, of course, Matthew Marks, David Zwirner, and Larry Gagosian in the 1990s and 2000s. You have to understand that one’s memory is challenged when trying to retain more than a few names in the annals of art history. It’s a bit of the same problem as regards the gallery owners. At any given moment, there are at least three-hundred contemporary art galleries active in NY. Among those three hundred, there are at least fifty that constitute the hard core, and in that core, there are about ten showing the most important artists of a given moment, dealing with a very large number of collectors, and possessing a very significant amount of power to influence press.

I’m going to resort to another sweeping generalization, but at any given moment you can indeed observe three categories or three levels of galleries. At the bottom of the pyramid, you have the small galleries that are linked to young artists. There you have the people who will do the studio visits and will try to identify and exhibit new talent. In the middle of the pyramid, you have the medium-sized galleries that will take over the young artists who have been noticed, have begun to have a market for their works, and whose career is taking off. Such galleries will expand those artists’ market and increase their visibility, will give them greater means, and will, perhaps, garner some museum exhibitions as well as induce higher prices. Finally, on top of the pyramid you have the big galleries working with established artists who have a given market and whose works are already in major collections. Each level has advantages and disadvantages and is linked in each particular case to the personality of the gallery owner or dealer.

I suspect that it is well known that galleries are always a personal affair. Whether it’s a small, medium or large enterprise, each gallery is linked to the vision and to the actions of a single individual and ceases to exist once the individual is no longer there. I know of no exception to the rule that the passing of a dealer leads to the discontinuation of the gallery’s existence under the same name except that of the case of one family, namely the Wildensteins.

Betty Parson

Sydney Janis

Leo Castelli

Geographical location

In New York, as far as geographical location is concerned, you can observe three moments. In the beginning, in the 1940s, and all the way to the 1960s, the galleries were positioned in the neighborhoods of the Upper East Side and 57th Street. Those were the places with the largest concentration of wealthy people in the former case and of businesses in the latter. These two locations continue to exist and to be active. Following that period and starting in the late 1960s, young or smaller galleries, as well as those that required more space to deal with the increasing scale of art works, instigated a movement toward Soho. Of course, Soho was favored as living quarters by artists themselves on account of low commercial rents and the significant stocking facilities the spaces allowed. Soho’s development continued until the mid-1990s when numerous galleries began what became a migration to Chelsea. That change was due to rising costs and to the gentrification of the Soho neighborhood, which slowly became residential and very commercial. Chelsea’s development began therefore in the mid-1990s and continues till today with every likelihood that it will last another ten years and will expand further south toward the meat-packing district. In Chelsea as in Soho, incredible real-estate development has followed on the heels of the galleries’ implantations. There have been, I would say, two additional moments, with the Lower East Side in the 1980s and Williamsburg in the 2000s–but in those cases without there being real endurance over time or significant stability in the marketplace.

I would like to delve now into some aspects of the life of art galleries I consider primordial for their existence. I’d say that there are seven of these: relationships with artists, with collectors, with museums and other nonprofit institutions, with the press, with finance, with the auction world, and with art fairs. And I will begin, of course, with the artists.

Relationships with Artists

Relationships with artists are, as you might imagine, never simple. In reality, it’s never the art historian or the critic who discovers and presents an artist. It’s always the gallery owner who takes the risk and the responsibility of offering one or two shows and of promoting the work to collectors over a period of several years. It depends on the artist, and I’d say that it’s the case for photography and sculpture more than for painting, but the galleries offer all sorts of agreements and often finance a portion or the entirety of the production of a piece. There was a time when contracts were signed between artists and galleries for exclusive representation. I would place that period between the end of the 1970s and the early 1980s. Before then and afterward, it was very rare to have written agreements. As far as promotion of an artist is concerned, one has to remember that Leo Castelli was the first gallery owner to distribute works by his artists to galleries across the US and Europe; indeed, he invented that system of promotion. Castelli is also credited with having invented what we call the “star system” in the visual arts world, with artists thereby approaching the status of rock stars or movie stars. That system became generalized in the early 1980s, especially in such galleries as Mary Boone’s or Jeffrey Deitch’s with the artist Andy Warhol, of course, then Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Francesco Clemente, and, a little later on, Jeff Koons.

So far as I know, it is very rare for a dealer to dictate to the artist what he should do. At the same time, it’s very rare to leave to the artist alone the promotion and management of his work opposite collectors and museums. Once the artist begins to acquire a certain amount of fame, one has to be very careful with exhibitions abroad, be it in another gallery or in a museum. One or two wrong shows and it can be the end of a career before that career even starts.

The relationships a dealer builds up with his artists strongly resemble love affairs, which have their highs and lows, their jealousies, and their breakups. In the contemporary-art world, dealers risk seeing an artist take a direction–that is, create works–that won’t be accepted by collectors, that doesn’t produce enough works, or that will simply lead to him doing something else and deciding to abandon his career. The same thing goes for artists, who may see the interest of a dealer decline, a gallery close for financial reasons, or something else of the sort.

Relationships with Collectors

Relationships with collectors are the second pillar that supports the existence of an art gallery.

There are three types of collectors, defined in terms of the level of their means. People know the big names. (In the 1970s, for example, people would know of the Sculls, the Tremaines, the Panza di Biumos, the Rockefellers, etc.) But galleries don’t just function with big collectors; they require a very large number of smaller ones in order to operate over the long run. Everything is and has to based on mutual confidence and respect, with relationships that are built up over a period of many, many years.

As far as collecting is concerned, let us look at New York again in historical perspective. Very briefly, in the 1940s and 1950s once again what one saw was a combined interest in European and American art. Starting in the 1960s, there was a gradual shift toward American art per se and an increased interest, on the part of Europeans, in what was happening in New York. Support for contemporary art was expressed first and foremost by women of wealthy families and, more gradually but eventually firmly, by the men, too. In the beginning, it’s always about decoration, but once all the walls are filled one moves to the use of storage. The role of the galleries was and continues to be one of education and, secondarily, one of placement of works in “good” collections.

I cannot but continue to repeat the importance of legislation. For the majority of the collectors of contemporary art, more often than not the works represent assets, some of which will increase in value and can be used to pay for part of what is due to the IRS. Amounts of varying size can be deducted. Many a collector uses contemporary art as a game: buy a lot and early and then help increase prices before reselling through galleries or auction houses. There is, of course, as I mentioned before, an array of fiscal incentives in the US that encourage one to use part of one’s capital or works of art to support nonprofit institutions.

The fact that New York has long been one of the largest financial centers in the world means that there is an incredible concentration of capital in this city. The only other city that can today aspire to an equivalent position, and a dominant one at that, is London. Until the end of the 1970s, the socioprofessional groups that filled the ranks of collectors were to be found among doctors, lawyers, and members of the business world. From the late 1970s onward and as the role of the business and financial sectors increased (with speculative consequences that have become much greater than before), there was, owing to the increase in the number of people capable of acquiring works and of entertaining a relationship with the contemporary-art world, a concomitant increase in the number of collectors.

In any gallery’s history, there is an incredible proportion of silence. There are also an astounding number of little stories that together go to sum up what will become art history. The internet has entailed an absolute revolution as regards the way business is conducted and the number of people who can be reached. However, it is my feeling that a personal relationship with the collector remains indispensable–one based on chemistry, that is. There are few deals that occur without the purchaser actually seeing the work. And very few deals take place without the existence of a personal relationship; indeed, that sort of relationship becomes especially unavoidable when the sums in question start to become very large.

Relationships with Museums

Galleries’ relationships with museums are synergetic and evolve over time. For New York starting in the 1930s, the Museum of Modern Art has been the most important component in the promotion of contemporary art, and that is so not only on account of the exhibitions organized in New York but also and predominantly so through the exhibitions it toured around the US at first and then throughout the world a little later on. We’re talking here about thousands of exhibitions sent around the US and dozens of shows whose tours were organized between the end of World War II and the early 1970s. As I was saying before, museums depend enormously on galleries in order to be able to function. On the one hand, they help museums locate new artists and, on the other hand, they facilitate museum acquisitions. As far as the relations between gallery owners and MoMA are concerned, I would like to read the following quote from Sybil Gordon Kantor’s Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modem Art (Cambridge, MA and London, England: MTT Press, 2002), p.93:

Barr was repeatedly helped by those European dealers who emigrated to the United States in the 1920s, such as J. B. Neumann, Pierre Matisse, Joseph Brummer, Valentine Dudensing, and Karl Nierendorf. But he turned primarily to the persuasive radical art champion Neumann . . . to further his education in modernism and to secure material, books, and reproductions for his course. Neumann also was a source for the current gossip of the art world for Barr’s modern art class.

I would also like to read the following excerpt, this one from Michael C. FitzGerald’s book on Picasso and the art market,

Many of them [curators, museum directors, art critics, and collectors] were deeply involved in the wide-ranging business of the marketplace. Moreover, the market was not peripheral to the development of modernism but central to it. It was the crucible in which individual artists’ reputations were forged as critics, collectors, and curators joined with artists and dealers to define and confer artistic standing.

In this expansive program, museums became both an integral part of the venture and the ultimate forum for accreditation. As the campaigns of artists and dealers became increasingly successful, the number of institutions receptive to modern art expanded in Europe and especially in America. With considerable sophistication, dealers extended their activities to join with directors and curators in developing audiences around the world. Generally working behind the scenes, dealers and their artists orchestrated museum exhibitions that raised the leading twentieth-century artists to the rank of modern masters (Michael C. FitzGerald, Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century Art [Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1996], p. 4).

Purchasing works done by an artist and staging an exhibition for him in a museum are some of the best ways of increasing the visibility of and underscoring the breadth of consensus around such work. That said, if you look closely at the financial statements of museums over time, you will quite easily discover that curators have very, very limited funds for acquisitions and for making any sort of serious mark on the market. They depend to a great extent on the trustees, who are in fact the ones going to buy or decline purchase of works destined for the museum’s collections. In that sense, I find myself obliged to advance the following argument: that the relative weight of curators has diminished over time. It’s the administrative personnel, on the one hand, the collectors and donors, on the other, who seem to have gained the upper hand and who now control to an enormous extent the program of acquisitions and exhibitions. One should not be duped as to the why and how of this change. Ten-million dollars can buy you a seat on the board of the Guggenheim or of MoMA. It goes without saying that you can act in one way or another to promote the artists who are part of your collection, pay for an exhibition, or even fund a retrospective for the work of an artist in whom you’ve invested substantially, so as to see his prices go up before you cash in on your investment by selling the works on the market or by making a donation that will give you a nice tax write-off, should you happen to be paying taxes in the US.

For many years, galleries would remain behind the scenes, helping curators locate works needed for a show and sometimes helping find people willing to pay for the shows. Starting in the 1990s, there has been a steady erosion of a variety of means to pay for museum activities, most notably that of big companies such as Philip Morris. One only needs to look at the acknowledgment pages of exhibition catalogues to see the facts. There has also been a progressive retreat of public institutions, from city to state and federal government, which now focus a lot more on the construction of museum buildings than on activities that garner only some temporary visibility. For all these reasons, museums have been obliged to look for and obtain financing from the galleries themselves. Two recent examples are the retrospective of Richard Prince’s work at the Guggenheim and Takashi Murakami’s at LA MoCA.

You will certainly find indications of these changes printed in various newspaper articles from the 1970s and 1980s, but I would say that it has been during the present decade that one has witnessed the fall of all the masks. On that account, but also due to curators’ inability to do their job without having their arms twisted, museums have lost a great deal of their credibility in establishing the canon of art history. As nothing–well, almost nothing–now remains hidden, galleries have little by little taken over from museums the role of being arbiters of taste, and they have done so not only on account of their gigantic footprint but also through exhibitions and publications that are extremely savvy and at times of equal if not better quality compared to what museums do.

Relationships with the Press

As far as the press and art criticism are concerned–here again, I am engaging in sweeping generalizations–I would say that there was a very long period of time during which the critics possessed unlimited power. That was true mostly in the 1940s and 1950s, with, of course, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. Starting in the late 1960s, one can observe a decline in the critic’s importance that continues on today. Such decline is in some respects the result of the increasing number of art historians who receive diplomas and work their way into journalistic circles as well as of the increasing number of magazines that deal with contemporary art. New York displays, without a doubt, an incredible amount of creativity when it comes to artistic coverage, but the critic’s job only attracts people who already enjoy a certain level of income and who can put up with the absolutely ridiculous low paychecks in this field. With the advent of the internet era, there was of course an explosion of internet sites that came to be added to the print media (dailies as well as magazines and other periodicals). This phenomenon, of course, has contributed further to the decline of the critic’s role in the art market. One way or another, and like it or not, very few sales depend on a good or bad word from an art critic; for, after all, the people who can buy art have absolutely no time to read and be influenced by authors.

Let’s be honest. It’s the art market that allows magazines to exist by paying for their costs through advertising. You need only compare the share of advertising in an issue of Artforum from the 1970s to that of today to understand what I’m talking about. Beyond any editorial prerogatives they may exercise, magazines need to kiss the hand that feeds them by occasionally publishing reviews of shows organized by the galleries that foot their bills. Things here are quite clear and there is very little sentimentalism. Of course, the dealer can make use of this or that article to illustrate the fame of an artist, and an article in a magazine can lead directly or in due time to the sale of one or many works. But what counts more than anything else–as it always has–is the museum exhibition catalogue, which is an imperative tool for promotion and sales. To all this I must add two parenthetical statements. The first one concerns the New York Times, which has continued to play a very active role in the promotion of contemporary art and has done so in a way that has been equaled only in London. The second remark serves to remind us that the press is and will continue to be an indispensable tool of communication. Besides the invitations a gallery sends out to announce an exhibition, the monthly press has been, is, and will continue to be the best way of introducing future exhibitions and of putting forth an image of the artist’s work.

Relationships with Art Fairs and Auction Houses

I will cap off my presentation with mentions of two final components that play a very important role for galleries in New York as well as everywhere else: art fairs and auctions.

As for art fairs, it has been since the 1980s, if not before then, that some fairs have become impossible to avoid. Paris’s International Contemporary-Art Fair (FIAC) has played a very important role for a long time, as has Art Chicago, but the 1990s and the 2000s have been dominated by Art Basel. That is the place where one can see, in a single location, what is happening in the market.

As far as art auctions are concerned, it was starting in the 1970s that they gradually introduced and separated out postwar and then contemporary art as distinct sales categories. The auction houses not only help one take the market’s temperature but, above all, they set the prices. They are the only place where things are public, whereas you all know very well that galleries will never let you know their turnover or what they sell and for how much.

Another conclusion relates to the future, and it’s more an observation than anything else. We live in a globalized world. Chinese art and Indian art are enjoying increased importance and are beginning to command serious prices–and at times absolutely incomprehensible ones, at that. New York continues to be an amazing and very special place. But as far as I’m concerned, there is no capital anymore. There is now a multiplicity of centers. And at any given location, you know that you are missing something happening somewhere else…

Georges Armaos studied contemporary art history at the University of Paris I (the Sorbonne). He received his Ph.D. in 2002 after defending a dissertation that compared the French National Museum of Modern Art at the Pompidou Center to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He has been contributing articles, essays, and interviews to art reviews and learned journals in Greece, France, and the United Kingdom since 1995. Starting in 2003 he has immersed himself in the contemporary art market, working in Paris (Xippas Gallery), Los Angeles (Christopher Grimes Gallery) and New York. Currently based in New York City, he works for the Gagosian Gallery.