Among the things the French Revolution changed were also the mores of the art world as it had been organized around the Académie royale de peinture (French Royal Academy of Painting). With the emergence of sociétés d’amis des arts (societies of friends of the arts), new forms of public exhibitions, and the development of subscription as a method of financing for cultural works, the game being played out among the various agents involved became increasingly open, and this began to take place even before 1789.

The amateur, or lover of art, stood at the center of this process of transformation. After having devoted a key work to the subject in 2008, Les amateurs d’art à Paris au XVIIIe siècle, Charlotte Guichard here shows us how.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Is the Love of Art a Form of the Pasion for Equality?

The Arts Worlds Tested by the French Revolution

Charlotte Guichard

In his report on the 1767 salon, Diderot indulged in a long tirade against the “race of amateurs.” This social and political critique, since become famous, was aimed at the old monarchical system of arts that was organized around the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (French Royal Academy of Painting). The challenge to this traditional form of patronage for artists and then its sudden disappearance during the French Revolution were the occasion to rethink the ties between art and society, between artists and their sponsors, and between the art work and its audience.

Support for the arts and for artists did indeed take on new, sometimes unexpected, and often experimental forms between the years 1780 and 1810—which thus alters our view of the revolutionary break that took place and also shows the limits to a kind of historiography that often remains focused on the distinction between state commissions and private commissions. The emergence of Sociétés des Amis des Arts (Societies of the Friends of the Arts), the invention of unprecedented forms of public exhibitions, the development of subscriptions` are so many experiments that partook in a new articulation between art and society starting in the late 1770s. These forms of associations were not the fruit of artists’ own efforts or those of state institutions; they were linked with a key figure, that of the amateur (lover of art). What they invite us to do is investigate in a different way how political and social changes that took place during the Revolution transformed this figure of the amateur and invented new forms of artistic patronage.

Art and Sociability: The Experimentation of New Forms

In the late eighteenth century, the public space for art was monopolized by the Académie royale de peinture. While it was the case that too overtly commercial kinds of arts exhibitions were condemned, the forms of sociability extant among elites appeared, on the other hand, as a privileged terrain for experimentation. Painting and sculpture were even of central importance to the system created at the first museum founded in Paris (1779)—the Établissement de la Correspondance générale sur les sciences et les arts (the Establishment for General Correspondence on the Sciences and the Arts). This museum operated on the basis of a weekly assembly of individuals who came together around an exhibition of scientific, technical, and fine-arts objects (which took the name “Salon de la Correspondance”) and a periodical (Nouvelles de la République des Lettres et des Arts, News of the republic of letters and the arts).

As Francis Haskell has shown, this Museum invented the first temporary art shows in France. The year 1783 saw the opening of the first retrospective for the work of a contemporary artist, the seascape painter Joseph Vernet, followed closely on by the first historical exhibition of the masters of the French School of painting. The limitation on these shows, wherein resides also their novelty, is that they relied entirely on the temporary loan of works by their owners, who had agreed to bring out pictures from their private collections:[ref]Nouvelles de la République des Lettres et des Arts, March 26, 1783. Nineteen owners of Vernet pictures agreed to participate in this exhibition that brought together forty-nine of the painter’s paintings.[/ref] “All of the above pictures are from the exhibition room of the Count of Orsay, who wished to allow the Public to enjoy them. This distinguished Amateur’s passion to be of use to the Arts and the sumptuous Museum he has arranged for them at his home are well known.”[ref]Ibid., June 8, 1779.[/ref] This demand to bring things out into the public eye [exigence de publicité], which is associated here with the figure of the amateur, broke with Parisian elites’ traditionally more private forms of sociability. And it was to become increasingly prevalent in the following years. For, in the face of the success of such exhibitions, the Salon de la Correspondance opened its doors to the public at large, so that one no longer needed to be coopted or introduced by an existing member as a requirement for admission.

Fig. 1 : Arnaud Vincent de Montpetit. Portrait of Louis XV, 1774. Oil on glass; 74 cm x 62 cm, Château de Versailles.

A bit of everything could be found at the Salons de la Correspondance. Among the exhibits for May 11, 1779 were a model of a mill, a grain threshing machine, a picture by Louis Trinquesse, another by Simon Vouet, and a portrait of Louis XV by Arnaud Vincent de Montpetit, the inventor of a new kind of varnish (Fig. 1). Yet the hybrid format of this show made the exhibited art works seem less dignified in character, contaminated as they were by the lesser status of the other objects. In wishing to bring a form of sociability originally destined for elites toward a broader public, this museum put to the test the monarchical system of arts—which explains the fact that it was banned in 1788. It shows the dynamism of private initiatives in the worlds of art but also the antinomic nature of two models, that is: the Academy-based model, which preserved the hierarchy of objects and audiences, and the cultural-enterprise model, which was supported by urban elites attracted by novelty.

Subscriptions: Reinventing Artistic Patronage

Fig. 2 : Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Voltaire nude, 1776. Life-sized marble statue; Louvre Museum.

One is in the habit of presenting this museum, still insufficiently examined by art historians, as an exception. And yet, this undertaking [entreprise] fits into a broader context concerning the way in which, beyond the model of state patronage or individual commissioning, one rethought how artists were to be supported. In some initiatives, one endeavored to alter and update the traditional forms of artistic patronage by imagining a private yet collective form of commissioning: subscription. The most famous example in the art worlds is the subscription for the statue of Voltaire by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle. The project came into being in 1770, in the salon of Madame Necker, around seventeen men of letters who, including Diderot (Fig. 2), had initiated the project. Ultimately, more than eighty subscribers participated in the statue’s financing. While not public, this subscription remained in keeping with networks characterized by a high-society form of sociability [la sociabilité mondaine]. To be found therein were men of letters, monarchs such as Frederick II, governmental ministers, and, more surprisingly, professors of mathematics from the École Militaire (French military school).[ref]Guilhem Scherf, Pigalle. Voltaire nu (Paris: Somogy, 2010).[/ref].

During the Revolution, the subscription method was used to alter and update in a lasting way how commissions were granted. At a distance from the practice of one-off subscriptions—the emblematic example of which is the one proposed in 1790 for Jacques-Louis David’s Serment des Horaces (Oath of the Horatii)—the Société des Amis des Arts made this method a key feature of its reform program.[ref]Udolpho van de Sandt, La Société des Amis des Arts: un mécénat patriotique sous la Révolution (Paris: ENSBA, 2006).[/ref]. Founded in 1789 by the architect Charles de Wailly, the Société des Amis des Arts was supported by a “subscription of twelve-hundred amateurs, each of whom would give a sum of just fifty pounds a year.” The Société des Amis des Arts testified, first of all, to a continuity with the forms of sociability extant under the Ancien Régime and the aristocratic model of the amateur: among the subscribers, members of the financial community were quite numerous, as were lawyers, notaries, and architects. While continuity with the Ancien Régime was affirmed, the Academic figure of the amateur was given new legitimacy through the use of a vocabulary based on citizenship and patriotism. Take the introduction to the 1792 catalogue: “The Society . . . does not conceal from the public that it needs to be aided in the execution of this praiseworthy plan by the lofty and benevolent class of amateurs. Were one merely to have the satisfaction of having contributed to the good and to the honor of one’s country, the opportunity the Society affords to the public will still be a felicitous one for the genuine friends of the arts, for wellborn souls, and for good citizens.” This vocabulary based on citizenship and country, placed side by side here with the ideal of the amateur, was well suited for the reinvention of a private form of protection that had become collective in character and to a change from a monarchical form of patriotism to a liberal one.

Fig 3. Louis-Léopold Boilly, Houdon’s Studio, c. 1804. Oil on canvas; 88 cm x 115 cm, French Museum of the Decorative Arts.

Opposite the Jacobin and Davidian view on how the Arts were to be reorganized, this Society represented a liberal way of conceiving social organization, whose emblematic painter would be Louis Boilly (Fig. 3). The Société des Amis des Arts experienced some real success, reformed its statutes in 1817, and continued its activity, on a renewed basis, through to the late nineteenth century. It was part of the general rise of the scholarly forms of sociability that were destined to develop during the nineteenth century, and the existence of such forms allow one to relativize the extent of the revolutionary break that occurred between the Age of Enlightenment and the Guizot moment. This type of association, which demonstrates the dynamism of a private cultural policy coupled with efforts in the state sphere, suggests that it is advisable to nuance the stark opposition between the French state cultural model and the private cultural model said to prevail in England.[ref]This view is also suggested in Holger Hoock’s work, The King’s Artists: The Royal Academy of Arts and the Politics of British Culture 1760-1840 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003).[/ref]

Taste Communities: Reexamining the Role of the Amateur

The amateur is omnipresent in these stagings of artistic patronage. Mobilized for very different and apparently paradoxical ends, he is sometimes seen as a genuine model in his own right, sometimes as a foil. While not challenging the Bourdieusian reading, which considers taste to be a form of distinction, neither does the latter allow one to grasp in full the social and political stakes involved in the love of art. Far from being neutral and disinterested, the amateur is an eminently political figure born at the heart of the monarchical system, and that is where this figure is to be placed from the outset—not in the world of the market and of private collecting, where one is usually in the habit of summoning it up. The term amateur appeared for the first time in 1694 in the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, and it was within the setting of the Académie royale de peinture that this figure took on its social and political force and became charged with a normative dimension.

Fig 4. Nicolas-Guy Brenet, The Death of Guesclin, 1777. Oil on canvas; 383 cm x 264 cm, Louvre Museum.

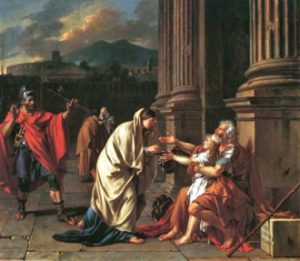

In 1748, the Academy theorized the status of the honorary amateur as the norm for the arts public. This status constituted a riposte to the birth of a public and critical space for art, in the Habermassian sense. In the Academy’s conception, the amateur is connected not to the public space but to the high-society and aristocratic space of forms of sociability: he patronizes artists but does not participate in public art criticism. The amateur is political, for he is supposed to favor the development of the French School of painting. This “royal patriotism” (David Bell) was implemented by the government in its iconographic programs celebrating national history (Fig. 4) and appropriated by elites (such as David’s Bélisaire, purchased by the Prince-Elector of Trier; see Fig. 5). It was nonetheless exposed as a failure by the Salon critics, who advanced another reading of patriotism in the arts: publicity of collections open to all, end to the system of private patronage, and criticism of genre painting.

Fig 5. Jacques-Louis David, Bélisaire Begging for Alms 1781. Oil on canvas; 288 cm x 312 cm, Palace of Fine Arts, Lille.

During the Revolution, private elites continued to claim inspiration from the model of the amateur while applying a new patriotic discourse to that model. In following these transformations of patriotism, one better understands what seems at first sight to be a paradoxical articulation between the royal patriotism of the collecting elites of the Ancien Régime and the liberal patriotism that developed during the time of Revolution: this articulation sheds light on the figure of Antoine Lavoisier, who commissioned work from David and who was also one of the subscribers to the Société des Amis des Arts. Thus do two highly compartmentalized historiographies—a social history of collections under the Ancien Régime (Colin Bailey) and a history of the worlds of art in Revolution (Thomas Crow)—meet up at this juncture.

These experimental forms of artistic patronage remind us that, in the eighteenth century, the category of the amateur corresponded to a new way of thinking about the social sphere. Being an amateur, or rather presenting oneself as an amateur, signified reinventing a social identity for oneself that was predominately art-related. This category designates individuals coming from varied social horizons (financiers, the noblesse de robe and the old nobility, merchants) who were united by a shared passion. The love of art made possible a form of social fluidity that, even though it was fragile and ephemeral, was always in performance and was removed from the status hierarchies that characterized society under the Ancien Régime. As Bernard Lepetit wrote, men are not marbles in separate boxes: with the amateur, the social history of art can take into account the “pragmatic turn” of recent historiography and account for a new approach to the constitution of social identities. This pragmatic reading of the amateur invites one to adopt another way of understanding the connection between art, society, and politics on the basis of a more refined measurement of the social sphere and starting from objects and works, as well as the associations they may produce, instead of from overarching and predefined hierarchies.

With the elimination of the Académie royale de peinture, the amateur was to lose his regulatory power as new figures (the collector, the dilettante, and the critic) emerged that were, in turn, going to link up with the ways in which the worlds of art are represented. The collector was going to take on responsibility for the patriotic dimension—as was shown in the case of Charles Sauvageot, who bequeathed his collection to the Louvre in 1856—while the amateur was to be cast back into the private sphere of good taste and forms of entertainment devoid of symbolic value.

Bibliography

AURICCHIO, Laura. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009.

BAILEY, Colin B. Patriotic Taste: Collecting Modern Art in Pres-Revolutionary Paris. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2002.

BELL, David. The Cult of the Nation in France: Inventing Nationalism, 1680-1800. Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press, 2001.

BORDES, Philippe, and Régis MICHEL. Eds. Aux armes et aux arts! Les arts de la Révolution: 1789-1799. Paris: A. Biro, 1988.

CROW, Thomas. Emulation: Making Artists for Revolutionary France. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

GUICHARD, Charlotte. Les amateurs d’art à Paris au XVIIIe siècle. Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2008.

HASKELL, Francis. The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

LEPETIT, Bernard. Ed. Les formes de l’expérience: Une autre histoire sociale. Paris: Albin Michel, 1995.

POULOT, Dominique. Musée, nation, patrimoine: 1789-1815. Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

Charlotte Guichard is a Research Fellow at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS; UMR 8529/University of Lille-3). A former student at the École Normale Supérieure (Fontenay-Saint Cloud), she specializes in Early Modern Art History. She has published Les amateurs d’art à Paris au XVIIIe siècle (Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2008) and edited “Les Formes de l’expertise artistique en Europe, XIVe-XVIIIe siècles” (Revue de Synthèse, 2011, no. 1).